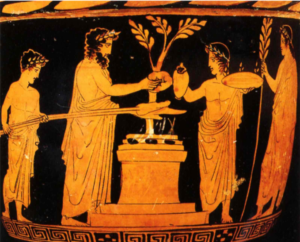

Ritual Practices among Armenians: Offerings

Continuing the examination of various forms of the ancient sacrificial offering ritual, here are some excerpts from Yervand Lalayan’s article titled “Ritual Practices among the Armenians”:

“…As a first offering, gifts of wheat, flour, oil, cheese, butter, olive oil, grapes, and wine were freely given to both friends and the church, including its clergy. Gradually, these offerings led to the establishment of the following church taxes:

PTGHI (First Fruits) – In favor of Etchmiadzin, wheat was collected throughout Russian Armenia during harvest time, approximately one pood (about 16 kg) per household, while in the jurisdiction of the Aghtamar Catholicosate, it was about half a pood per household for the benefit of Aghtamar’s Holy Cross Monastery. In this region, only those who owned a bed, i.e., married individuals, were required to pay this tax. They were exempt from it only when they were no longer in the ‘fruit-bearing’ stage, meaning they were no longer capable of having children. If someone refused to pay this tax, the collecting priest would curse them, saying, ‘May you not bear fruit.’

To collect this tax, vardapets (scholarly priests) and official priests would go around, preaching in the churches. As a gift, they too were given a few poods of wheat, which was called “gavazanaptugh”—literally, the fruit of the staff—referring to the staff held by the preaching priest or the one who holds authority.

During the same harvest period, the parish priest, along with the sexton, would bless the threshing floors of their parish and receive as a gift about one pood of wheat and half a pood of barley. This offering was called “kalaptugh” (the fruit of the threshing floor), while the sexton would receive approximately a quarter pood or a small basket of wheat.”

These passages offer insight into how offerings and taxes in Armenian religious tradition were intertwined with agricultural practices and social obligations, reflecting a deep connection between the spiritual and material aspects of life.

In cities and large towns, instead of collecting the wheat tax, sextons would go around every Saturday carrying a large basket on their backs, shouting, “Sexton’s bread, dear ladies of the house!” Each household would bring and give an entire loaf of bread.

This custom has also faded, but in some places, such as Old Nakhichevan, Kaghzvan, and Van, the same practice continued only during the seven weeks of Lent. Each household would voluntarily take a loaf of bread to the church weekly and give it to the sexton. If someone was reluctant, the sexton would go to their house and demand it. This offering was called “Yotnahats” (Seven-bread).

In Javakhk, an old tradition has also persisted: the godfather (of a child or marriage) was obliged to gift a pair of shoes to the village head, and in return, the head was required to donate his old shoes to the sexton.

Cheese – In spring, after the Feast of Ascension, agents would spread out to the villages, collect one day’s worth of milk from the sheep, make cheese, and send it to Etchmiadzin. The same was done in the jurisdiction of the Aghtamar Catholicosate.

Oil – In the fall, agents would again visit the villages and collect one or half a pound of oil from each household in favor of the Mother See. The same was done in the Aghtamar region, but in addition, they also collected a pair of socks from each house for the monks of Aghtamar.

Oil and Hemp – During Lent, in the Aghtamar Catholicosate, they collected oil, hemp, and cotton as a tax for the church. The oil and cotton were used for lamps, and the hemp was used to make ropes, both for hanging the lamps and for use on the monastery’s boats.

Wine – When a wine press owner first produced new wine, he would not only share it with his relatives, the priest, and the village elder, but also take a couple of pitchers to the church as “bazhki”—wine to be used for communion during the liturgy. Many old churches had buried clay jars next to them, where this wine was stored. In many places, when wine pressing began, the priest would come to bless the press, receiving grapes as a token of gratitude.

Flour – The first time new wheat was milled, some flour was sent to the church to be used for making the Eucharist bread.

Grapes (ԽԱՂՈՂ) – On the Feast of the Assumption of the Holy Mother of God, every vineyard owner brings 5-10 pounds of grapes to the church. A portion of the grapes is blessed and distributed to the congregants, while the rest is given to the priests and the church attendants.

Butter (ԿԱՐԱԳ) – On Holy Thursday, during the “Washing of the Feet” ceremony, each household brings a “khiar,” which means a butter shaped and sized like a cucumber, to the church and gives it to the priest. A small portion of it is blessed by the priest and distributed to the people, while the remainder is kept by the clergy.

Chickens (ՀԱՎ) – During the Catholicosate of Aghtamar, it was customary in the autumn to collect 1-2 young chickens from each household as a tax for the benefit of Aghtamar. According to common tradition during Easter and the Feast of the Holy Cross, people would bring gifts for the Catholicos of Aghtamar, such as lambs, eggs, baked goods, sugar, and roasted chickens. Many would also give offerings known as “ajhamboor” (a respectful kiss or blessing).

Soul Offering and Seizure (ՀՈԳԵԲԱԺԻՆ և ԿՈՂՈՊՈՒՏ) – In the past, each monastery would send one or two clergymen once or twice a year to the villages within its diocese to collect “soul offerings” from the relatives of those who had died that year. These offerings could include lambs, sheep, cattle, or money, and they would also take the deceased’s bedding and clothing as part of what was called a “seizure.” This no longer happens, but instead, on the anniversary of the deceased, a ruble or more is requested as a “soul offering” for the church’s benefit.

…”The firstborn calf of cows and buffaloes is customarily and continues to be donated to the church.”