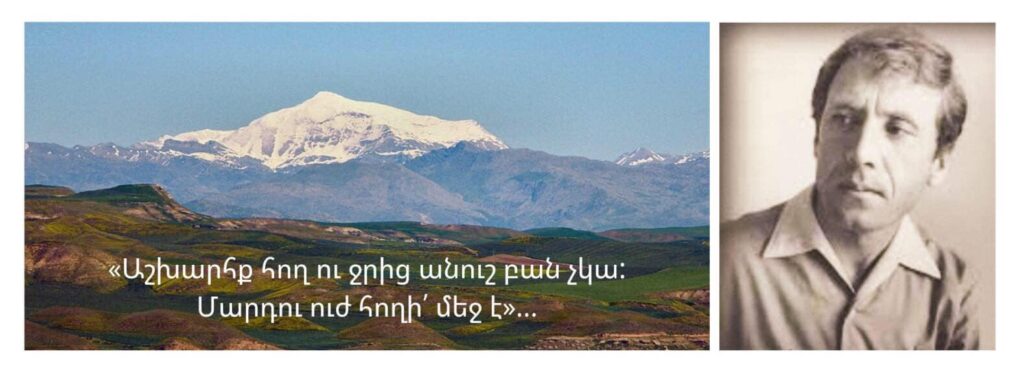

«DAVO»

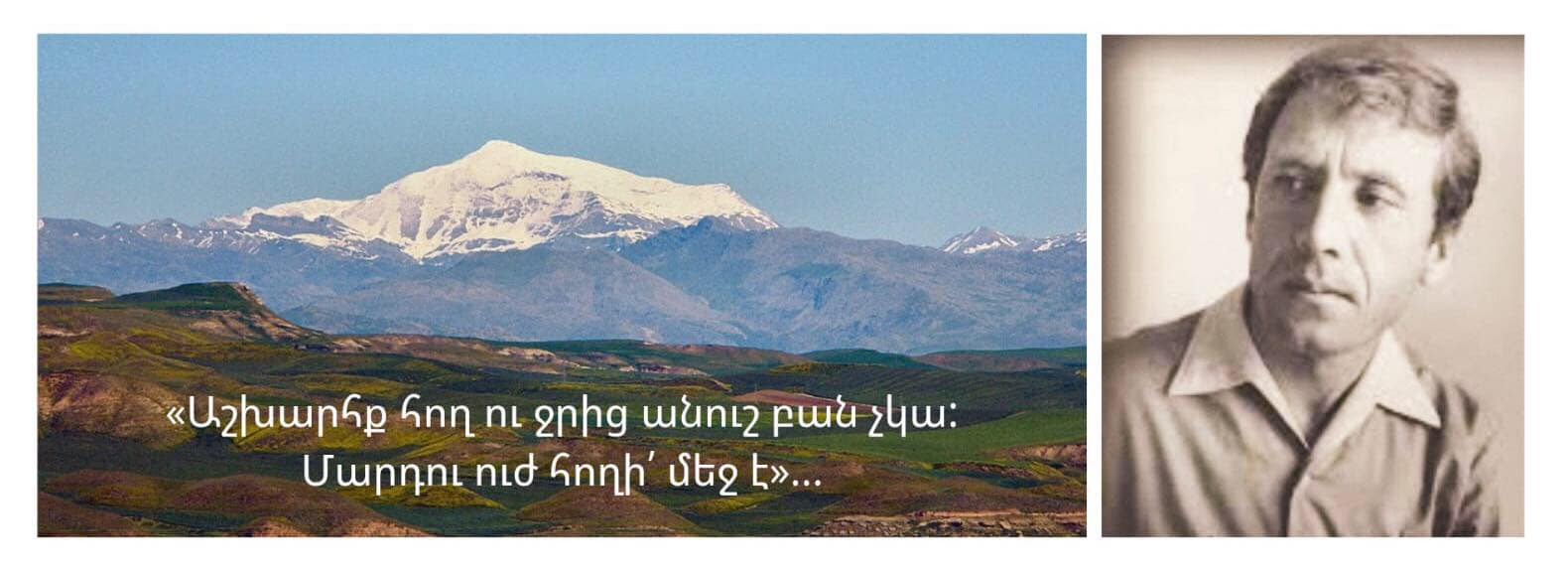

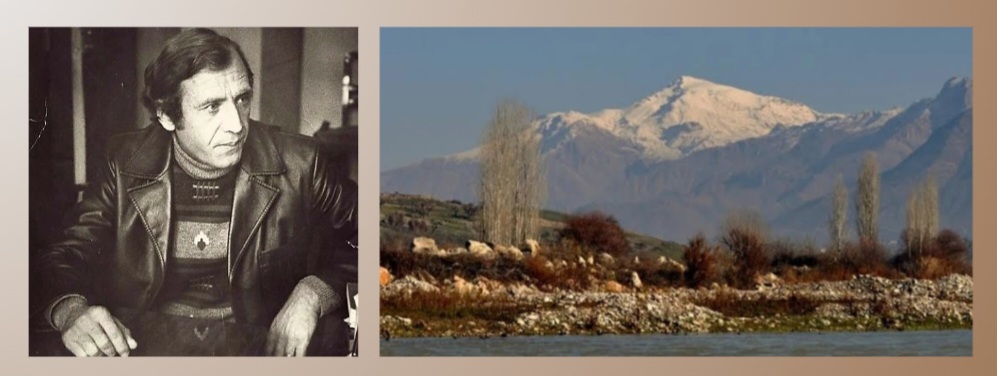

Firm as the homeland’s soil, pure as water, are the figures crafted by Mushegh Galshoyan—true children of their ancestral land, steadfast in their struggles, their fates intertwined with an unquenchable longing for home, and hearts aching with loss.

“Longing—oh, how mighty it is! There’s nothing stronger than longing in the world.

With longing, sorrow deepens. Ah… longing is sorrow, tender—tender sorrow.

And that sorrow…

That sorrow gives birth to greatness, magnifies the soul, and transforms a person into a giant, a hero.”

“There is nothing sweeter than earth and water in this world.

A person draws strength from the soil!

As long as the earth under one’s feet remains theirs, they are undefeated; but once taken, they are enslaved.

The greatest loss in the world is that of a human being.

The loss of a person is irreversible. The loss of homeland and soil is grievous, but soil is eternal; it will never yield to another master.

The soil shares its lifeblood with its rightful owner, awaiting its kin—waiting and waiting until one day, they are reunited.”

(Mushegh Galshoyan, “The Myron of the Gorge”)

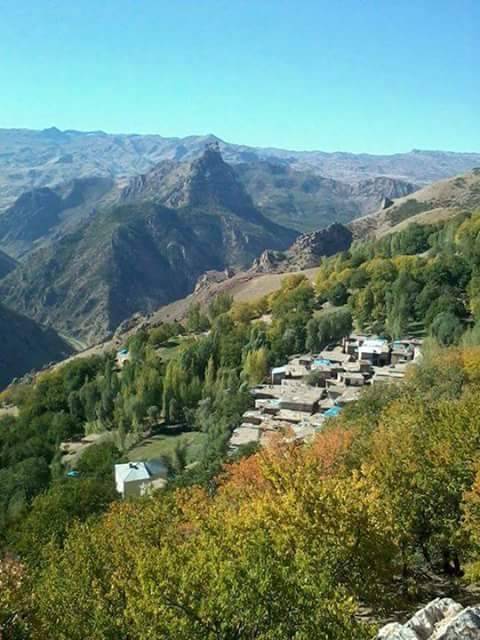

In Mushegh Galshoyan’s masterful depiction, “Davo,” one of General Andranik’s most loyal allies, spends his final moments envisioning Sassoun, reliving his heroic battles and burning with vengeance.

“…The soil shares its lifeblood with its rightful owner, awaiting its kin—waiting and waiting until one day, they are reunited…”

“Davo,” with a heart ablaze with longing and vengeance, unfolds below:

DAVO

“On a bed spread across the earthen floor lay Davo. His face freshly shaven, dressed in brand-new white garments—purchased last year, set aside for this day. Today, he wore them and reclined in his spotless bed, his body resting calmly. His eyes were half-closed, arms stretched out across a floral quilt, the buttons of his shirt undone, the white hairs on his chest tangled like frost, bowing thoughtfully.

Through the window came a single strand of sunlight, as if sent to carry Davo to the heavens. The sunbeam coiled around him, teasing the white hairs on his chest and his broken white mustache, flickering red and blue before his half-closed eyes, gently tickling his eyelids.

Davo remained silent. Only his eyelids seemed to speak, engaging in a quiet dialogue with the light. The beam that played on his forehead and eyes, along with the red and green glimmers dancing on his lids, whispered of something—a memory, a moment, or a longed-for dream.

Davo’s trembling lids and furrowed brow seemed to search…

The old men of his village surrounded him.

That morning, when Davo asked to be dressed in his white clothes and for his bed to be laid on the ground instead of the platform—and sent his son to call for Pchuk, his old comrade-in-arms—everyone understood: Davo was setting out on his final journey.

And so, the village elders came, gathering around him.

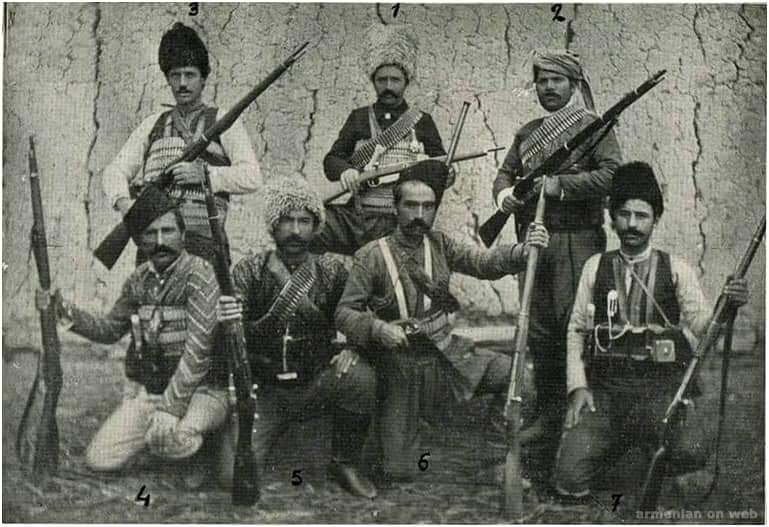

Hamze Pchuk, the blacksmith, arrived first; then Grigor from Mokh, kin of Gevorg Chaush; followed by Avé from Bjni, Manuk of Khbljoza, Miron from Khut, Tigran, and Mosen from Hitenk.

They all came. Davo was departing.

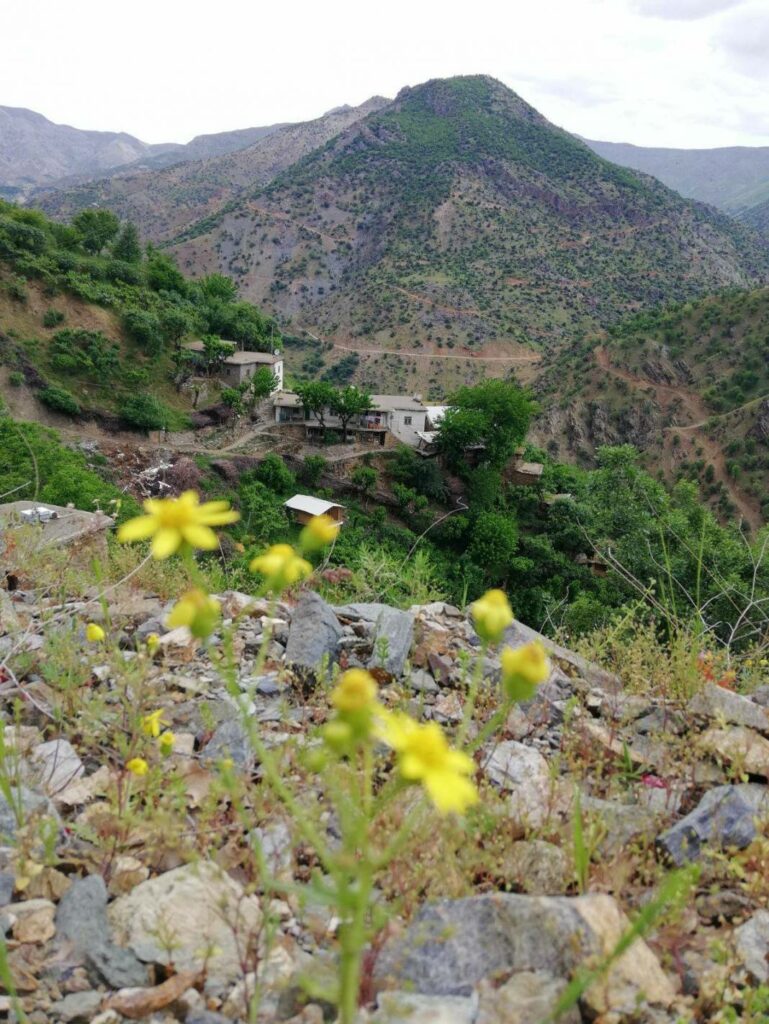

Davo, who once kissed the sword in place of the cross at Maruta Monastery, was leaving. Soon, his breath would merge with the winds of Maruta Mountain, and the aged eagle circling Kablorakar’s peak would pluck a feather from its chest. That feather would flutter in the fiery hues of dusk over Talvorik’s skies.

Hamze Pchuk, stepping inside, called out:

—Davo! Wrecked house, are you truly leaving? Are you going?

Hamze Pchuk repeated the question, kneeling beside his friend’s bed.

—Will you leave me behind, Davo?

Davo reached out, clasping his friend’s hand. Pchuk was astonished:

—Such strength still flows in your veins, Davo. Where are you going?”

“To the battlefield, Pchuk,”

Davo thought to himself, and suddenly… he recalled…

What he had been searching for with such intensity—he found. That forgotten story from long ago, which the light dancing in his eyes whispered of, the red and green glimmers swirling before his lids—it all came rushing back to him.

The Battle of Tsitskar.

He remembered and clasped his friend’s hand even more firmly.

“Do you recall, Pchuk, the Battle of Tsitskar? Does it stir in your memory?”—a smile eased the tension from his wrinkled face.

“There’s joy written on your brow, Davo,” noted Hamze Pchuk. “Are you heading home?”

“To battle, Pchuk. Will you join me?”

He felt as though he could speak aloud, yet he couldn’t understand why his mouth wouldn’t move.

“What does your heart desire, Davo?” asked Mosen from Hitenk at an unexpected moment.

Davo groaned in discontent.

“My heart desires…” Then he strained to move his lips so Mosen might hear him, and he imagined he had actually voiced the words:

“Leave me be, Mosen. Let me…” And again, he gripped his comrade’s hand.

“To battle, Pchuk. Will you come? Whoever falls is a traitor… The Battle of Tsitskar—is it in your memory? Do you recall?”

2

The enemy was vast in numbers. They advanced relentlessly.

Their assault was fiercest on the left flank. To that side, beyond the enemy’s left line, lay a village. The villagers had gathered at its edge—clearly visible, men and women, young and old, raising a clamor to embolden their kin in battle. The clashing of metal, the burst of fireworks, wild howls—on the rooftop of a house, someone sang, their voice piercing and unyielding…

The chaotic roar of the marauding mob was insignificant, but the haunting, blood-soaked song dripping across the battlefield drove him mad. He could almost feel that song draining the strength from their left flank, as if it made the men there long to escape…

Where was Commander Andranik? Why wasn’t he bolstering the left flank with even a single platoon from the right or the center?

A low hill divided the fronts on the left, and whoever claimed the jagged rock perched at its summit would claim victory. It was obvious; no great commander was needed to grasp this truth…

Fighting shoulder to shoulder with Pchuk, his mind remained fixed on that rock—Tsitskar.

If only he and Pchuk could scale that position, take their place behind that stone stronghold.

If only they could turn into sparrows, slither as snakes, become…

He tugged at Pchuk’s sleeve.

“There’s no other choice,” Pchuk agreed.

“And no falling!” he bellowed, locking eyes with Pchuk. “Whoever falls is a traitor!”

Later… From the rock’s cover, his and Pchuk’s rifles thundered without pause.

“Whoever falls is a traitor!” they cried out in turn, without a moment to aim. There was no need to aim—the vengeance searing in their hearts exploded from the barrels of their rifles, crashing into the enemy’s cowardly ranks, silencing the song that had cursed the battlefield.

As the evening fell, the enemy retreated, and they entered the village.

The villagers had neither fled nor hidden, knowing that the army approaching their homes was Andranik Pasha’s—an army that would harm no soul. They greeted them at the village edge with bread and salt, the very spot where, all morning, they had stood cheering their kin with shouts of encouragement. Among the greeters were elders, women, children, and a young man—tall, with piercing eyes and a proud demeanor. Encircled by the crowd, standing a head taller, he smiled tenderly at Commander Andranik.

“Why didn’t you take up a weapon?” the commander inquired. “Why didn’t you join the fight?”

“I am not a man of weapons, Pasha,” the young man replied, his smile oozing with sweetness. “I only know how to sing.”

This? Was it truly this? Could it be?

A furious cry caught in his throat, red and green flashes danced wildly in his vision, and with a mad resolve, he drew his sword. Then came Andranik’s commanding voice: “Davo!”

“Pasha, do not hold my arm!” he bellowed, wild with rage, his gaze barely fixing on the commander’s face. Andranik’s visage appeared to him, surrounded by flickering red and green. “Grant me the right, Pasha!”

“Davo, the boy is beautiful and a singer. He must live.”

“And were the men and women of my tribe not beautiful, Pasha? Where are they? Did my tribe not sing, Pasha? Where is their song? Whether or not you grant me the right—I will kill him!”

3

“I will kill him, Pasha!” Davo’s voice broke through the air, defiant.

The others looked on in unease, and Bje Avo called out:

“Rise, rise, Davo! Talvorik fights! Why do you lie here, homeless one?”

Davo’s brows were tightly knit with discontent, his breaths heavy and labored…

4

“I will kill him,” he raged, and before he realized it, his blade had fallen, severing the young man’s head.

And then, as if it had been waiting, the commander’s voice thundered: “Death to Davo!”

“Pasha!” Pchuk stepped forward, standing before Andranik. “It is Davo!”

“Death to Davo!”

Other soldiers from Sasun tried to intervene—Manuk, Isro, Cholon, Akho—but the commander stood resolute.

“You are a brave soldier, Davo,” Andranik said. “I will remember you. But you have left me no choice,” he continued, his voice heavy with grief, his eyes filled with tears. “Accept your fate, Davo.”

“I will not, Pasha! Your judgment is wrong!”

“Disarm him!” the commander roared. “Bind him and throw him into the river!”

He selected four soldiers for the task.

Evening had fallen. Silent and head bowed, Davo walked ahead of the soldiers toward the river—Aratsani. The spring dusk was soft and tender, the ground warm beneath his steps…

The sun’s dying rays fell across his face and eyelids, drawing him westward.

If only he could keep walking like this, head low, unbroken, until he reached Mush, climbed the heights of Kepen, and ascended the summit of Tsirnakatar. Then he would open his mouth to cry out:

“Ehehee, Talvorik, I have arrived!”

5

— Eheheheee, Talvorik, I have arrived!

Davo’s lips moved once more, giving life to his memories.

From a distance, Davo’s voice echoed faintly, fragmented like the remnants of a song.

His comrades exchanged glances—Davo was leaving…

He was leaving, and with his final breath, he spoke.

— Eheheheee, Talvorik, Davo has arrived!

Grigor of Mkhtents cried out, his voice rich and melodic, and began to sing:

“The gurgling waters streamed down

From Mush’s lofty mountains…”

The melody stirred something in Davo’s heart. His wrinkles softened, yielding to a smile…

Perhaps Davo had not left after all—he was still here!

— Davo! called Hamze Pchuk. If you’re headed to the homeland, let us go together. Why go alone, displaced one?

— I am on my way to the river, to be cast into it, Pchuk. It is the Pasha’s command. Do you remember?

Davo’s creased brow and half-closed eyes trembled faintly, brushing against the golden rays of the sun…

6

He walked towards the west, the evening sun brushing his forehead and his eyes. If only he could keep walking, silently, steadily, until he reached Mush, climbed to Kep, and…

But at the banks of the Aratsani, they came to a halt. The punitive soldiers averted their eyes from him—and from each other. One nervously pulled out a cigarette case, and they sat by the riverbank.

The river flowed westward in a fierce torrent. Even without being tied up, there was no escaping those ferocious waves. They would sweep him away to join those said to have gathered downstream, clogging the river’s path, forcing it to overflow into the deserts of Arabia…

Sitting under the shadow of execution, he gazed at the muddy, agitated waves. No, it wasn’t fear of death. Davo had long since left fear behind. His fear had died the day on Andok’s summit, during the war council, when Petara Akho had said:

“If defeat is inevitable, better to light a great fire on Andok’s peak, throw ourselves into it, and burn together, becoming smoke over Andok.”

Davo had agreed with Akho… That day, Talvoriktsi Davo had buried his fear.

But here, at the Aratsani’s edge, terror gripped him. The waves seemed alive, as if at any moment a hand might rise from the river’s depths to accuse him, Talvoriktsi Davo; an eye, wild with fear, might stare him down; a little girl with golden hair might be cast into his trembling arms…

He leapt to his feet, as if struck.

“Why are you sitting around?” he yelled. The soldiers scrambled up in confusion.

“The army is marching! What are you waiting for?”

The soldiers hesitated, exchanging uneasy glances. One of them undid his belt.

“Davo, forgive us, but… it’s the Pasha’s command,” one said softly.

“The Pasha’s command is wrong,” Davo growled. “If you want to carry it out, you’ll have to take one or two of you with me—I won’t go alone!”

He lunged at the soldiers, grabbing two and dragging them toward the roaring river.

In the end, they all collapsed in a tangled heap on the bank, the river’s furious breath brushing their faces.

“Davo,” one soldier said shakily, “let’s make a deal. We’ll tell the commander the order was carried out. But you must not let him see you again.”

The soldiers stood and left. Davo stayed behind, lying face down on the earth, its spring scent brushing against his face, his eyes closed.

The sun had set. Dusk wrapped the fields and mountains in a soft sorrow. The Aratsani darkened as he lay there, motionless, feet pointed toward the river. He could feel its growing darkness, its turbulent waves churning, sending shivers through him. The river’s menacing breath crept up his spine, to his neck, clawing at his legs, dragging him closer…

He sprang up and looked after the soldiers.

They were retreating quickly; soon, they would rejoin the army, marching westward… westward…

“Whoever retreats is a traitor!” he roared after them.

He shouted again…

7

— Whoever retreats is a traitor!

Davo opened his mouth, and his voice echoed through the cave.

Hamze Pchuk, kneeling by his friend’s bedside, paused in confusion.

He glanced around, then looked at Davo. Wrinkles creased Davo’s forehead,

lines overlapping each other.

8

“Whoever retreats is a traitor!” he shouted from the riverbank,

hurling the words like a curse at the soldiers, unable to think of anything else to say.

For two days and nights, he wandered along the army’s trail.

Rejected by the shepherd—cast out like a stray dog,

he dragged himself behind the herd, guarding the army’s rear like a loyal hound.

The army was advancing slowly but steadily, moving west and then southwest.

From dawn to dusk, he nervously watched the troops’ formations,

trying to decipher the commander’s strategies and predict the battle’s outcome.

He felt that if he let his mind wander, the army—

for whom he had become a watchful guard—might suddenly falter or retreat.

On the third morning, the lines of the battlefield seemed wrong to him.

The enemy had retreated overnight, securing a crescent-shaped hill,

a highly advantageous position.

In such scenarios, Andranik would always investigate whether the enemy’s rear

was exposed or fortified.

And so, Davo set off to fulfill Commander Andranik’s orders.

He crept into the enemy’s rear and returned by nightfall.

He brought back valuable spoils—a sword, a dagger,

and a bridle-less horse. No longer a stray dog,

he was now a soldier who had returned victoriously from a daring reconnaissance mission.

By evening, the positions of the fronts appeared unchanged from the morning,

but from the pattern of gunfire, he sensed his comrades’ weakness.

Their shots were sporadic—a sign that the commander had ordered them to conserve ammunition.

“If that’s the case, it’s time for a charge, Pasha!”

And he raced toward the army.

With his sword unsheathed, he charged forward, galloping through the ranks.

He passed by Commander Andranik’s post and shouted,

“The enemy’s rear is empty, Pasha! Empty!”

“It’s Davo!” the commander’s jubilant voice rang out.

“Davo!” he called again, his tone like a command. It was as though he had just signaled the charge.

As Davo galloped, he glanced over his shoulder…

Oh, Mother of Maratuk! Swords gleamed in the sunlight—they were advancing.

“Whoever retreats is a traitor!” he bellowed over his shoulder, then leaned down toward his horse’s ear.

Bullets zipped over his head and past his ears,

but he was certain he wouldn’t fall. Davo would not betray;

Talvorik’s Davo still had vengeance to exact. Sword held high over his forehead,

he charged toward the enemy, toward the west, toward the distant mountains shattered in the sunset.

9

Davo clasped his comrade’s hand tightly, and Pchuk marveled again.

“Davo! Such strength still flows through your veins, boy—where are you headed?”

“To battle, Pchuk. Don’t you remember?”

“What does your heart crave, Davo?” Hitenktsi Mose asked again, in his familiar way.

“What does your heart crave, Davo?” mocked Khbljoza Manuk, half-annoyed.

“Davo’s heart craves pears and apples. Davo’s heart craves honey and butter. Davo’s heart craves sherbet. Davo’s heart craves Baghdad dates. Davo’s heart craves Indian oranges. Mose, Davo’s heart craves a watermelon bigger than your head!”

“Aaaah, watermelon!” sang Hitenktsi Mose. “Cursed Yerevan, cursed market, watermelon…”

Davo groaned. He tilted his head as though to let go of Pchuk’s hand,

but instead, he clung even tighter. Then, setting his face straight once more,

he turned his gaze to the sunlight.

“Cursed watermelon,” Hitenktsi Mose sighed, his voice quivering with emotion.

“May my eyes go blind, Davo, if they ever see you like this again.”

10

Under the blazing summer sun, the market sprawled in dust—a tattered garbage heap swarming with orphans.

The orphans, scruffy and feral like stray dogs, wandered with wary glances,

yet snarled and fought each other mercilessly. They scrabbled over watermelon rinds,

snatched at scraps of grapes, and dived for a single tossed seed,

rolling in the dust as they clawed and bit one another for it.

Their dust-caked, bloodied faces turned toward the market. Among these ragged, faceless children, Davo searched for kin, a friend, or a familiar face…

It was hopeless, but he searched anyway.

Somehow, the orphans, those timid little scavengers, sensed they had nothing to fear from this hairy, disheveled man—

despite his wild, terrifying face being the fiercest they’d ever seen.

They swarmed him like flies, buzzing incessantly around him, not knowing why.

Davo stormed into the market.

Behind him trailed the scruffy mob of orphans. The market shuddered with fear and froze.

All eyes were on Davo. Who was he?

Where had he come from, in trousers made of goat hair, a long woolen belt wrapped tight around his waist,

his bare back draped with goatskin, his chest bristling with hair, his face buried in it, his bloodshot eyes full of fire?

Who was he, this savage man from another world?

But Davo didn’t look at anyone. He saw nothing.

He strode through the market, trampling over everything in his path, surrounded by the ragged orphans.

“Grab it… grab it… grab it,” he muttered—or was he growling? No one could tell.

Even the orphans didn’t understand his words, but they instinctively knew it was a call to raid.

They scattered in waves, grabbing whatever they could find—stuffing items into their pockets, cradling armfuls of goods,

and darting away, huddling behind the man who cursed the market owners to oblivion.

“Grab it… grab it… grab it,” Davo growled again as he plowed through the market.

But then he heard a whimper from behind. He turned to see a girl, no older than nine or ten, clutching a watermelon tightly to her chest.

She whimpered like a frightened pup, writhing on the ground, refusing to let go of her prize.

When Davo turned, the watermelon’s owner bolted, screaming for help.

Davo didn’t chase after him. Instead, he approached the girl, knelt beneath a sack of watermelons,

and before the stunned eyes of the market crowd, effortlessly hoisted it onto his back.

Just moments before, seven or eight men had struggled to unload the same sack from a cart, and now, this wild man carried it alone.

Under the burden of the sack, Davo disappeared. His goatskin garb, his unruly hair,

his fierce face, his fiery eyes—everything vanished.

All that remained was the image of a strong porter,

a sack of watermelons moving as if by itself, leaving the market.

But the crowd surged forward and brought him down.

Freed from their terror, the mob trampled Davo to the ground, pinning him beneath the weight of his load.

They stamped on him furiously in the dusty street.

The enraged market owners vented their fear by crushing him underfoot, determined to kill him and drive away the stray dogs haunting their market.

The orphans peeked out from their hiding places, whining softly.

Their mouths were stuffed with stolen goods, their throats choking with sweetness.

Davo could only hear their voices as his temples throbbed with the echoes:

“Grab it… grab it… grab it.”

The market owners jostled one another as they trampled him underfoot.

Davo lay silent and still.

Eventually, someone spoke up: “Enough.”

And the mob, their terror and panic now dissipated, returned to the market,

relieved and unburdened, back to their business.

Only Davo remained in the street, face down in the dust.

Passersby paid him no mind—or rather, didn’t even notice him.

In the dusty chaos of that provincial town,

he blended into the ordinary backdrop of the day.

But the orphans noticed. They knew who lay there in the street—

the one who had just embodied their freedom, their audacity,

the sweetness that now filled their pockets and throats.

There he lay, in the dust.

From various corners, they began to wail.

But somehow, they realized their cries were dangerous.

Their mourning, their noise, could draw unwanted attention.

So they fell silent, all at once, and understood instinctively

that approaching the market that day would mean trouble.

And so they scattered throughout the city.

Davo lay still, unwilling to move, refusing to rise.

The earth drank in the groans of his weary bones,

while the blazing sun poured healing rays over his mangled back,

a strange, soothing balm. Why open his eyes?

Who was there to see? What was there to see?

And where would he go if he rose?

Better to die here, in this warm, dust-laden cocoon

that seeped into his bones, filling them with its bittersweet ache.

If this was to be the end—if every battle was destined to end in defeat—

then he should have planted his last bullet in his chest

and fallen on Andok, or on Black Mountain,

or at the foothills of Tsovasar, or on the slopes of Kablorakar,

or into the sweet, clear waters of the Talvorik River.

That’s how it should have been.

Yes, he should have faced the enemy’s bullet head-on

or spent his last on himself and fallen there, where it mattered.

But that chance had slipped away.

And it was his fault—Talvoriktsi Davo’s fault—

for letting the perfect moment and place for his death pass by.

Now, he deserved this—a pitiful end in the dusty streets.

Still, Davo refused to move. He didn’t want to.

And then, from a distance, as though in a dream, he heard his name:

“Davo!”

11

“Better for my eyes to go blind, Davo, than to have seen you like that day,” Mosen of Hitank whispered, his voice heavy with sorrow.

The old men gathered around Davo knew the tale well, but Mosen still tried to recount it. Yet Hamze Pchuk bristled in frustration.

“Stop your useless rambling! Is that the Davo you choose to remember? Don’t taint his final breath!” Pchuk snapped, turning toward Mkhtanktsi Grigor.

“Sing a song for Davo!”

Davo’s furrowed brow softened once more with a faint smile.

Then Pchuk felt Davo’s fingers tighten briefly and leaned closer to catch his words.

“Pchuk…”

The voice echoed as if from a deep cavern.

Pchuk imagined hearing Davo’s voice reverberating from the caves of Kablorakar.

“Don’t… cross my hands,” Davo murmured. “Leave them open… let them stay open.”

Davo was already leaving…

Pchuk felt the faintest pressure in Davo’s grip, yet his eyelids still seemed to embrace the light. A beam of sunlight stretched from the window, pulling Davo gently toward the sky.

And Davo was going.

Through the ears of his galloping horse, with his blade bared to his brow, Davo charged forward.

He flew toward the ridge, toward the enemy’s positions…

The evening sun glimmered on his unsheathed sword, kissed his forehead, and filled his vision with fiery flashes of red and green.

Davo rode westward, toward the sun splintered across the distant peaks…

Mushegh Galshoyan (Մուշեղ Գալշոյան)

https://www.shutterstock.com/fr/video/clip-1110481663-batman-sason-mereto-mountain-peak