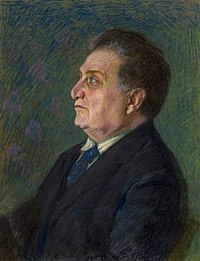

The eminent ethnographer Yervand Lalayan, in his article “Sacred Rites Among Armenians,” explored the origins and evolution of the “ritual of offering,” perpetuated among Armenians and other peoples around the world since time immemorial. Below, we present brief excerpts (the beginning was covered in previous articles)…

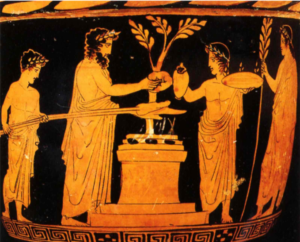

“Among the Greeks, there was a tradition where the services offered to the gods were the same as those needed by living beings; temples were considered the homes of the gods, sacrifices as their food, and altars as tables.”

In this context, it is possible to demonstrate that the food offerings made to the gods and those placed on the graves of the deceased share a common origin, as both derive from offerings made to the living…

“Among Armenians, when grapes are harvested for the first time (usually during the Feast of the Dormition), they are sent as gifts to relatives, the head of the household, dignitaries, the priest, and then brought to the church to be blessed, and the next day, to the cemetery for the commemoration of the dead. In the Shirak region and in other Armenian villages, during the first threshing, bread is made with flour from this wheat, called “chalaki” or “taplay,” which is offered to relatives, the head of the household, the priest, and distributed early in the morning to passersby as a portion intended for the deceased. When the first pears and early apples are harvested, they are sent as gifts to relatives, especially the son-in-law, the head of the household, the priest, and taken to the cemetery for the commemoration of the dead during Vardavar, placed in a bag or on a tray on the tombstone. All passersby take them, eat them, and pray for the deceased. When honey is harvested, a portion is reserved for relatives, the head of the household, the priest; candles are made from the wax and then brought to the cemetery and the church to be lit. A newborn lamb or calf is offered to relatives, the head of the household, or other dignitaries, consecrated to the church, or slaughtered to prepare the “bread of the soul.” The new wine is sent as a gift to relatives, the head of the household, or dignitaries, to the church for the communion chalice, and to the cemetery for the commemoration of the dead, where a little is poured on the tombstone before drinking a cup of mercy.”

The above-mentioned facts, observed in all countries, demonstrate that sacrifices are, by principle, offerings in the true sense of the word. Animals are offered to kings, slaughtered on graves, and sacrificed in temples. Prepared foods are offered to military leaders, placed on graves and on temple altars. The first fruits are offered to living military leaders, as well as to the dead and to the gods: in some places, it is beer, in others, wine, and elsewhere, chicha, sent to the visible ruler, presented to the invisible spirit, and sacrificed to the gods. Incense, once burned before kings and in certain places before dignitaries, is burned elsewhere before the gods.

Let’s also add that dishes, as well as all sorts of precious objects intended to gain favor, are accumulated both in the treasuries of kings and in the temples of the gods. We now arrive at the following conclusion: In the same way that offerings made to earthly rulers gradually evolve to take the form of state revenues, offerings made to the gods develop to take the form of ecclesiastical revenues.

“The Middle Ages introduced a new level in the development of offerings. In addition to what was necessary for the communion of priests and laypeople, without including what was intended for the Eucharist, it became customary to offer various gifts, which, over time, were no longer even brought to the church but sent directly to the diocese. Later, due to the frequent repetition and expansion of these gifts, which were supposed to be intended for God but were in reality bequeathed to the church, regular income for the church began to appear.”

Among the Armenians as well, the income of the church and its clergy has developed in a similar manner. Initially, pilgrims would willingly invite the church’s clergy to share their sacrificial meal, but gradually, they found themselves obliged to reserve a specific portion for the church and its clergy. Thus, nowadays, anyone offering a sacrifice is required to give the animal’s skin to the church, the right leg to the priest, and the head and stomach to the sacristan.

Spontaneous gifts of wheat, flour, oil, cheese, butter, olive oil, grapes, and wine offered to relatives, the church, and its officials gradually gave rise to ecclesiastical taxes, which we will discuss later.