HAYKAR

Or:

HACHAR – “A type of stone, originating from the land of the Armenians”…

The Armenian Highlands, famous for their therapeutic mineral waters, have also played a crucial role in the history of mining, metal extraction, and metallurgy, thanks to their vast natural resources.

Due to the presence of rich ore deposits, metal tools were already in use here as early as the 5th–4th millennia BCE. Ancient specimens have been uncovered on the shores of Lake Van, in the Angegh Tun province, in the Ararat Plain, and along the shores of Lake Urmia…

By the 3rd millennium BCE, Armenian Mesopotamia, Rshtunik, Julamerk, and Sasun served as the “metal storehouse” of the ancient Near East. Later, in the 2nd millennium BCE, they held a dominant position in metal extraction and exchange.

Excavations in Lchashen, Metsamor, Karmir Blur, and the regions surrounding Lake Van, the Erzinka Plain, and other sites within the Armenian Highlands provide evidence of an advanced metalworking tradition.

From ancient times, both Armenian and foreign historians have documented the wealth of Armenia’s mines and the exceptional quality of its valuable minerals.

Movses Khorenatsi, in his History of Armenia (Book I, 23), praises the Ancestors and glorifies the great Tigran, emphasizing how he expanded the “treasury” of gold and silver (“He multiplied the treasures of gold and silver…”).

The Roman writer, naturalist, philosopher, and military commander Pliny the Elder, in his 1st-century work Natural History, while discussing pigments and the minerals used to create them, mentions Armenia’s mines (“Mines of Armenia”) and the superior materials they produced.

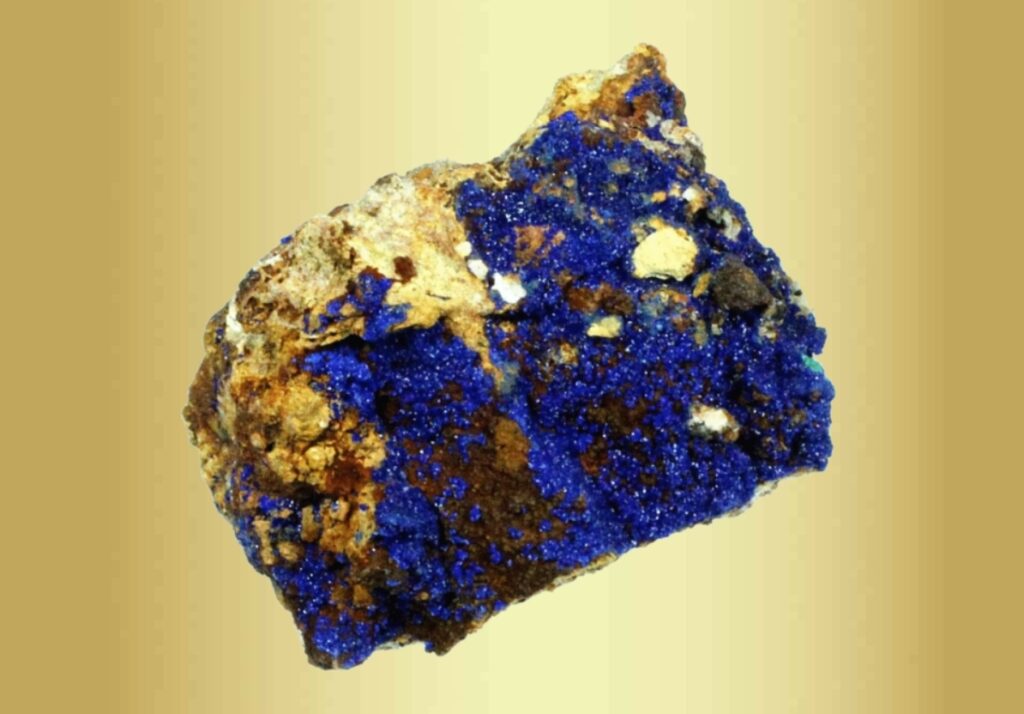

Lapis lazuli, with its mesmerizing, unfading deep blue, has been referenced in written sources since ancient times, including in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Traded from Egypt and Mesopotamia, it eventually reached Armenia, where it was surrounded by myths attributing mystical powers to it.

At the site of Ebla, an important Hurrian cultural center about 60 km south of Aleppo, archaeologists discovered 25 kilograms of lapis lazuli.

This precious stone was crafted using raw materials imported from Armenia.

For over 6,000 years, the famed Lapis Lazuli, known as the Blue Stone, has been valued as a symbol of protection, courage, success, and victory. It was believed to ward off evil and serve as a link to divine wisdom, enhancing spiritual awareness and enlightenment.

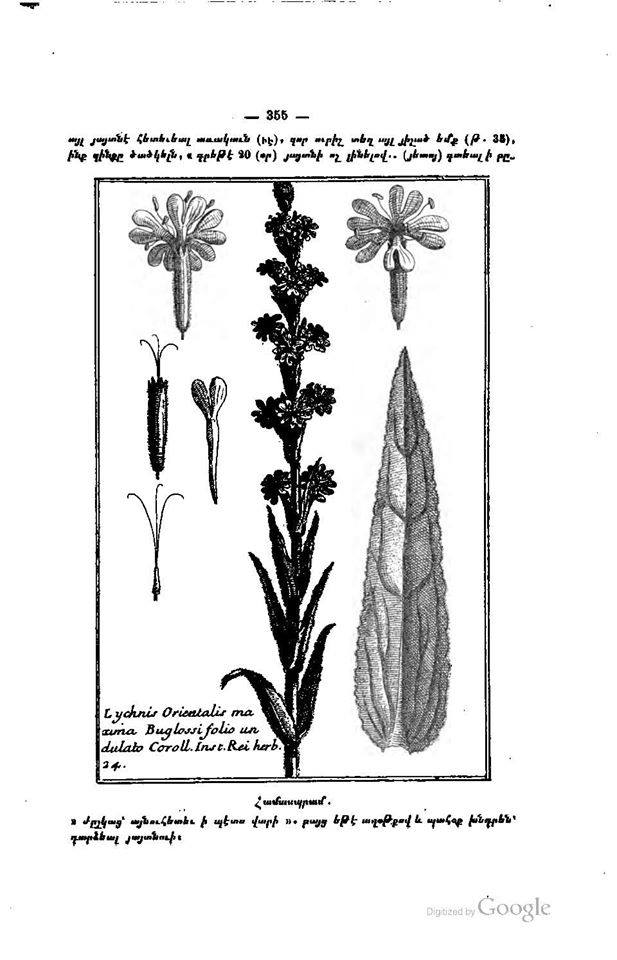

Theophrastus (371 BCE – 288 BCE), a notable Greek philosopher, naturalist, botanist, and alchemist, and a disciple of Aristotle, mentions Armenian stones in his writings on minerals, noting their use in seals and various applications. He also refers to a special “earth” from Cilicia, which, when boiled, became sticky and was used to protect grapevines from pests.

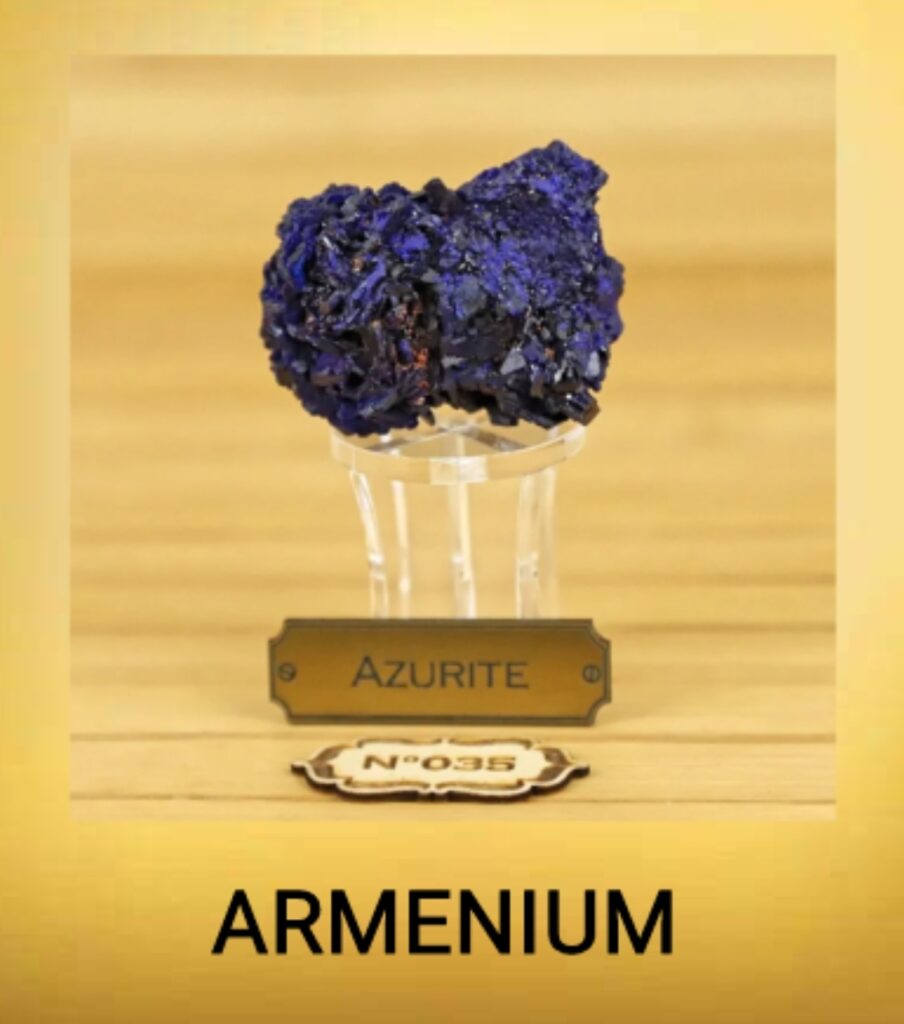

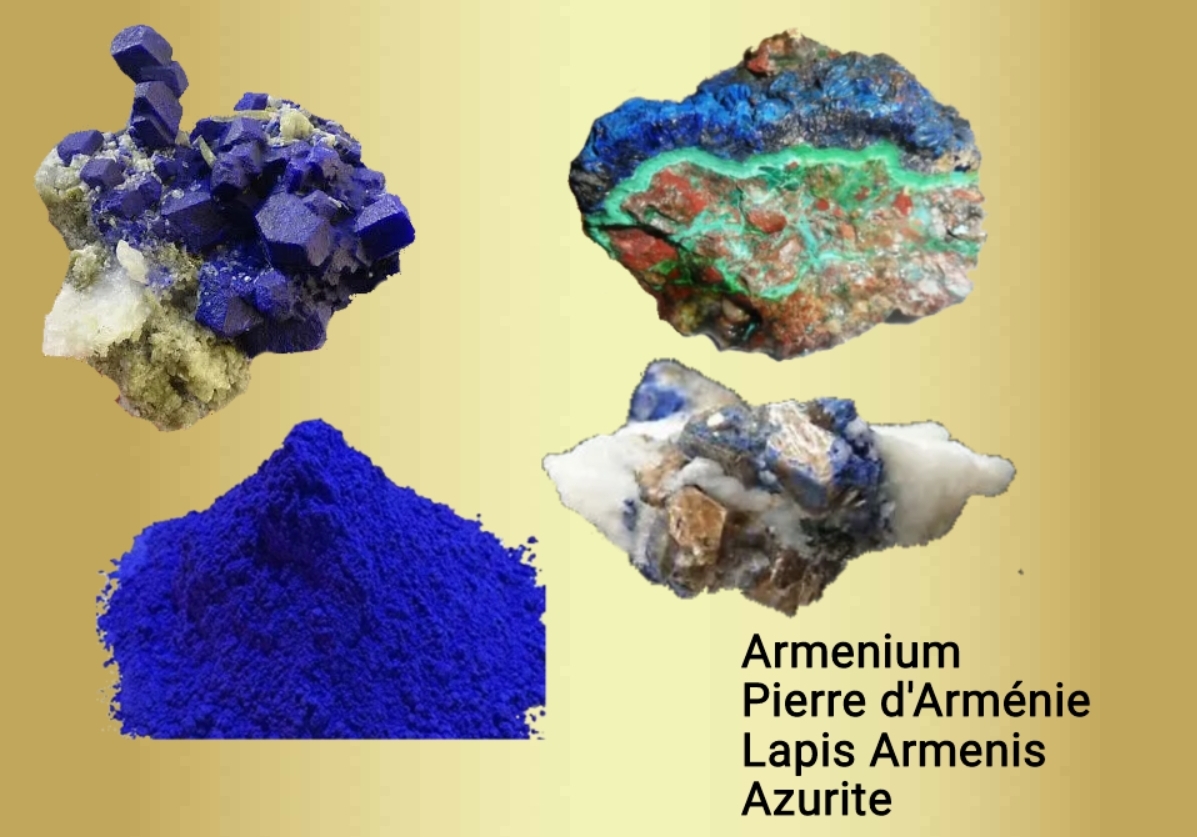

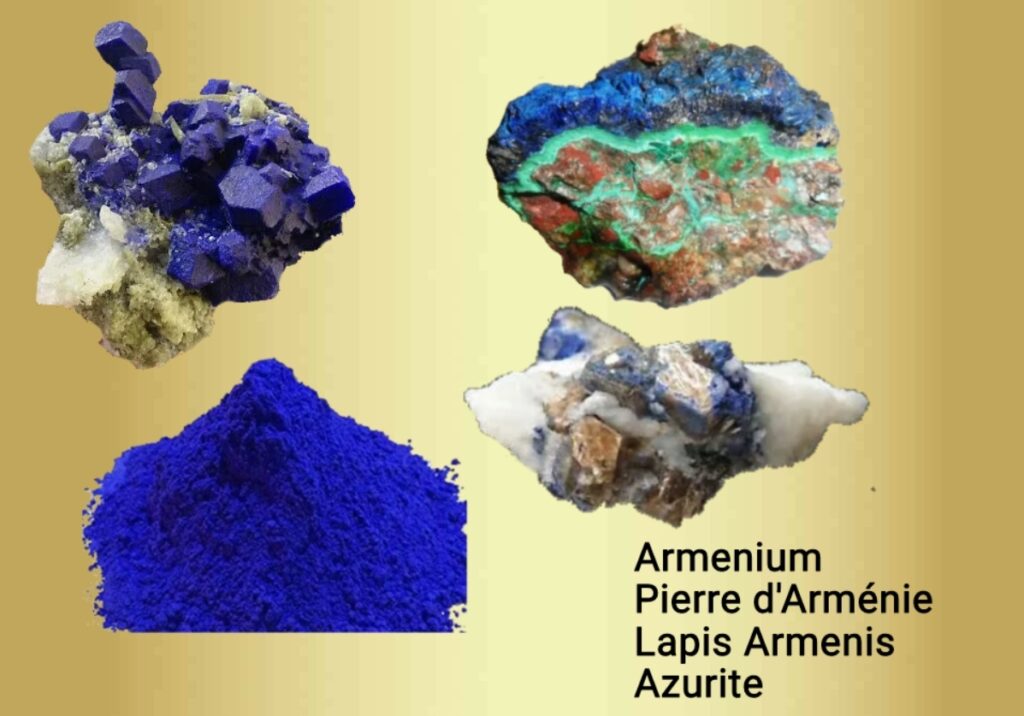

Theophrastus calls the famous Lapis Lazuli the “Stone of Armenia” or “Lapis Armenis”, also known as “Arménium” or “Haykian Stone.”

This name persisted throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, with the mineral often called “The Blue of the Mountains.”

In 1824, geologist François Sulpice Beudant named it “Azurite,” based on its deep blue color.

In medicine, the “Haykian Clay” (“Kav Haykian”), was known to Galen as “Haykian Earth.”

Various Armenian earths—some blue, golden, or reddish-yellow—were widely prized since antiquity.

Pliny the Elder mentions natural resources from Armenia, including palegues (Book 33, §15) and describes the finest Chrysocolla—with gold-bearing veins—as originating from Armenia (Book 34, §5).

In Book 35, he refers to Arménium (Azurite), writing:

“Armenia exports the material that carries its name. It resembles Chrysocolla, with the best variety being the one closest to it in deep blue hue…

In medicine, it is used mainly for hair treatment, particularly for eyelashes (bol d’Arménie).”

Since antiquity, crystalline bodies, composed of varied chemical elements such as copper, oxygen, and others, have intertwined to form new materials that accompany humanity.

One such crystalline mineral, copper arsenate (pghndzarjasp), known for its deep lazurite-blue hue, has been used extensively despite its high toxicity.

Apart from being crafted into talismans and jewelry, Haykar also served as a pigment.

Several colorless and colored stones and powders found applications in medicine, mirrors, and other fields—some of which are recorded in ancient Armenian dictionaries…

“Hachar—a type of stone originating from the land of the Armenians,” note medieval medical texts (New Dictionary of the Haykazian Language).

“Haykar—a variety of khazhak stone, bluish and soft, resembling gojasm.” (Arménite, Pierre d’Arménie – Armenite, Armenian Stone).

“Gojasm—a precious deep blue, opaque stone with golden veins; there also exists a yellow variety.” (Ligourion).

“Lajvard—an exquisite blue pigment extracted from gojasm.”

“Lajvard—a precious blue stone, classified among the flint family, once used to produce lajvard or lazurite pigment (Lapis lazulite).” (S. Malkhasyants, Armenian Explanatory Dictionary).