HAZARASHEN

also known as

“The Beam Passing Through the Skylight…”

Ancient creation myths highlight the triumph of Light over Darkness.

In discussing theories on the formation of the Universe and Life, Eznik of Kolb (5th century), in Refutation of the Sects, critiques the Epicurean idea of a “Self-Existing, Self-Sustaining World.” He illustrates the concept of creation by describing how dust particles in the air become visible when a ray of light passes through an opening.

(338) The Epicureans believe that the world exists by itself, like dust floating in the air when a beam of light shines through an opening, making the particles visible. They claim that the first elements were indivisible and eternal, and that through their condensation, the world formed—without God and without any guiding force shaping it.

Since ancient times, homes and religious structures throughout the Armenian Highlands have used natural sources of illumination, known as Loysijots or Lusantsuyts—roof openings (yerdik). Depending on the season, these were covered from the outside with waterproof layers of vegetation and soil, while in temples, a long pole-controlled shutter was used to regulate them from within.

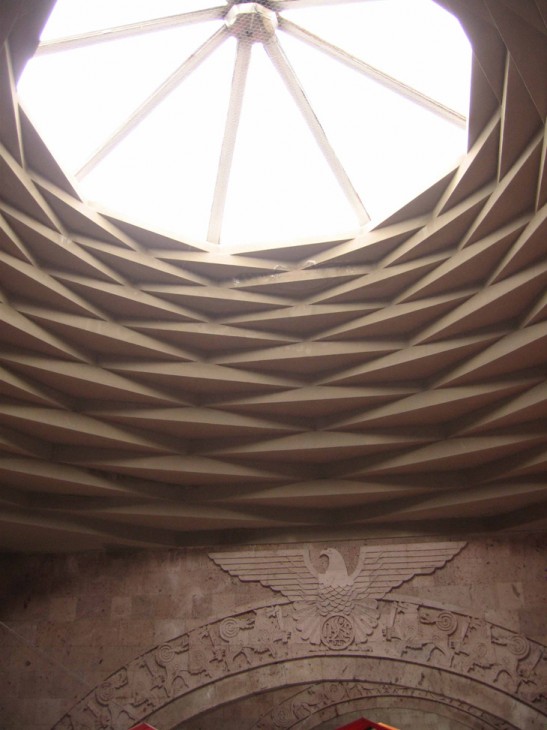

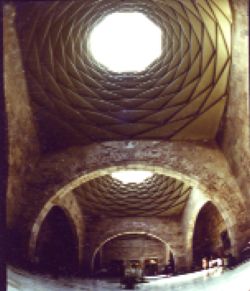

One of the most remarkable examples is the Hazarašen, a wooden structure built from thousands of beams, with concentric polygonal frames of short logs that gradually taper toward the yerdik.

More than just a source of light and ventilation, the yerdik symbolized “the household, its members, the family, the hearth, and its smoke.”

Armenian chroniclers (Eznik, Agathangelos, Buzand…) and later historians estimated population sizes based on the number of roof openings, a method known as smoke-counting. As Buzand recorded: “Twenty thousand Armenian households.”

The domed roofs of traditional Armenian homes, originating in ancient times, were built on wooden frameworks in two main styles.

The first style, simpler in design, consisted of log frames placed parallel to the walls and gradually narrowing toward the roof opening (yerdik), with rough wooden planks filling the gaps between them.

This type was commonly found in regions with abundant construction wood, such as northeastern Armenia, the Chorokh Valley, and the villages of Karabakh.

It had various names, including Kondatsatsk, Soghomatsatsk, Soghomashen, and more frequently Gharnavush, Gharnaghush, among others.

The second style had a more complex polygonal structure, made of concentric frames of short beams or logs that gradually shrank toward the yerdik.

This method was used in regions with little timber, heavy snowfall, and frequent rains, particularly in Upper Armenia. It was widely known as Hazarašen or Hazarašenk.

The term was most commonly used in Kars, Bayazet, Bulankh, Basen, Mush, Alashkert, Sebastia, Bayburt, Derjan, Sasun, Leninakan, Akhalkalaki, Akhaltsikhe, and surrounding areas.

Additionally, in some places, Hazarašen was called Dastatsatsk (in villages of Ghukasyan and Leninakan), Soghomak’ash (in Yeghegnadzor, Lori, and Shabin-Karahisar), Soghomak’agh (in Alaverdi), and in other regions as Syurmak’ash, Shushatsatsk, and more.

These terms were often used interchangeably for different roofing styles, mainly due to frequent population movements and resettlements.

Still, the most widely recognized and authentic name that has endured is Hazarašen, derived from the fact that its roof was built using “thousands” of wooden pieces. (As cited in S. V. Vardanyan’s study, “Hazarašen and Its Significance in Armenian Architecture”).

From ancient Armenian temples, where the sunlight illuminating the deity’s sculpture held great significance, to the earliest Glkhatun dwellings with central openings (yerdik) and hearths, to medieval palaces and modern structures, Hazarašen has, for thousands of years, drawn our gaze upward—toward the Unfading Light…

Photo by N. Chilingaryan.

At the Sardarapat Ethnographic Museum