In exploring the roots and subsequent developments of ritual offering traditions, the renowned Armenian ethnographer Yervand Lalayan cites the testimony of Movses Khorenatsi about King Yervand in his article “Ritual Rites among the Armenians”: “And Yervand offered abundant gifts and distributed money to each of them… And he did not become as beloved by those to whom he gave much as he became an enemy to those to whom he did not give with the same generosity” (Movses Khorenatsi, Book II, Chapter XXXV).

Let’s add a few more excerpts from the previously mentioned article.

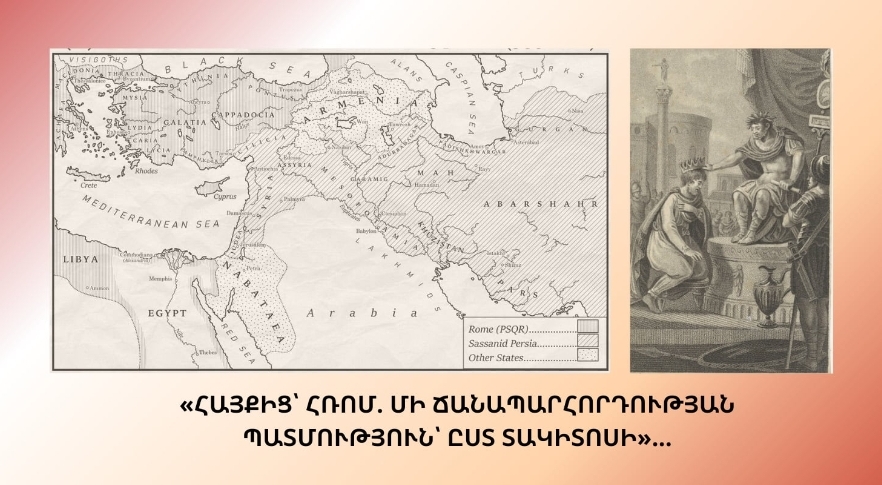

“Up until now, we have discussed the offerings that individuals of lower rank present in order to gain favor from their superiors. However, we have not mentioned the gifts that those of higher rank give to their subordinates. The difference in meaning between these two types of offerings is particularly evident in countries where the custom of giving is complex, such as in China.”

“During the visits that leaders make to their subordinates, or after these visits, there is an exchange of gifts. However, those given by the leader are called ‘rewards’, while those from the subordinates are called ‘offerings’. This is also how the Chinese refer to the gifts exchanged between their emperor and other states.”

It is necessary to say a few words about these offerings, even though they do not have a ritual nature. Over time, political authority strengthens and controls the entire society, but there comes a moment when it must relinquish part of this monopoly to its servants and subjects. The servants and subjects, initially obliged to make offerings, are now partially subdued by the rewards they receive.

“It is evident that as the offerings from subordinates gradually take on the role of taxes, levies, and customs duties, the rewards given by leaders turn into wages.”

“In Armenia, kings and nobles used to reward the services of their officers by granting them villages, towns, and even provinces, called ‘pargevanqs,’ to distinguish them from lands known as ‘patrimony,’ which were hereditary properties. The ‘pargevanqs’ only conferred the right to collect taxes for life.”

For military service, neither the soldiers nor the commanders received a salary but were rewarded solely by the spoils. In Mkhitar Gosh’s “Legal Code,” it is stipulated “according to custom” that half of the spoils must be given to the soldiers and that “if a soldier captures the equipment, horse, and weapons of the enemy during a war, all of this belongs to him, but the armor belongs to the lord, the copper and iron and similar items to the soldiers. Gold, jewels, and precious fabrics in all circumstances belong to the king, and valuable silver items and fabrics to the lords, while lesser value silver and fabric items belong to the soldiers” (Mkhitar Gosh, “Legal Code,” Part II, A).

During the time of the Armenian meliks as well, neither the soldiers nor their captains (yuzbashi) received any salary, and the melik was obliged to distribute part of the spoils to them and, during festivities, various “khilats,” mainly clothing, horses, and weapons.

The table of kings, nobles, and meliks has always been open to visitors and servants. Phaustos Buzand says: “Among these peoples and the humble, those who were called agents were honored by being seated before the king, allowing the great chiefs and stewards, who were only nine hundred agents, to enter at the time of the temple feast to sit at the table, leaving those who waited standing in the service of the agents.”

Employees of certain modern public institutions, such as clerks, public weighers, bath cleaners, and sacristans, do not receive a salary but are rewarded with gratuities. For example, clerks receive a few kopecks for the New Year and a few eggs for Easter. Similarly, barn cleaners receive half to a pound of wheat, with the latter reward having become mandatory.

In both Kars and among the residents of Alexandropol, Akhalkalaki, and Akhatsikhé, it is customary for women working in public baths, the cleaners, to visit the homes of the bathhouse clients during the New Year. They are received and given a plate of dried fruit and 10 to 50 kopecks. When the new bride goes to the public baths for the first time, after being washed, the cleaners solemnly knock their basins together while leading her out of the baths, and one of them presents her with a basin of water. The new bride must drink a little of this water and place money in the basin as a gift for the cleaners.

Public weighers take a small portion of the fruits and foods they weigh.

It is also worth mentioning the gifts exchanged between individuals who are not in a relationship of superiority and subordination.

“Among Armenians, exchanging gifts between equals is very common. For almost every major holiday, gifts are exchanged, especially between families newly united by marriage, and some of these gifts are considered so obligatory that they are sometimes strictly required. It is also common in our culture for parents to give something to their children for the New Year, children to give something to their parents, and for relatives to exchange gifts. At Easter, it is very common to exchange red eggs. Young fiancés often give a decorated egg to their fiancée. During the Transfiguration festival (Vardavar), it is common in many places to exchange bouquets of roses as well as decorated apples with fiancées. (Here is how the apples are decorated: before they ripen, without picking them from the tree, leaves cut into various shapes or with initials are attached. The covered parts remain white, while the rest turns red.)”

Gifts exchanged between newly allied families through marriage, known as “p’ay” or “khoncha,” are particularly noteworthy and are considered absolutely mandatory. Thus, even if the wedding is held early, some of the main “p’ay” are still required. The “p’ay” or “khoncha” are sent from the groom’s home to the bride’s home during the Barekendan festivities, the first day of Lent, Mid-Lent, Palm Sunday, Easter, Vardavar, and Navasard. The “p’ay” consist of food, drinks, and various ornaments. In return, the bride’s family also sends various foods and drinks to the groom’s home, which is called “darts’vatsk.” Socks are almost always included among the gifts sent from the bride’s home, as they are a fitting gift for this occasion and many others.

In family life, certain gifts have also become obligatory forms of tribute. For instance, during childbirth, relatives are expected to send a “tsnndgavath,” which primarily consists of various dishes and pastries. The groom’s family gives the bride a monetary gift called “yeresttesnouk,” and the bride’s family gives the groom a similar gift. During the wedding, a monetary gift is also given to the bearer of the crown. Food is sent to the home of the deceased, a lamb and a black cloth are offered for the Holy Cross. Cakes are sent to someone going into exile, and upon their return, they also bring a gift.

Thus, the offerings that the early humans voluntarily presented to those from whom they wished to gain favor have, over time and with the development of society, become the source of many customs. The reason for presenting gifts to political leaders is explained by the fear they inspire and, in part, by the desire to obtain their help. These offerings, which initially attracted favor through their intrinsic value, later became symbols of loyalty and devotion.

Offerings of the second category evolve into donation rituals, while those of the first category first become taxes, then tributes. At the same time, the custom of placing food on graves to appease spirits develops, repeating on the graves of notable individuals and eventually becoming sacrifices on temple altars. Meat, drink, or clothing initially seen as beneficial to spirits or gods come to symbolize submission. Offerings transform into acts of respect regardless of their intrinsic value, allowing priests to subsist as intermediaries of divine worship, with sacrifices originally serving as church income. Thus, we have another example of how religious rites precede political and ecclesiastical structures, as the actions derived from rites lay the groundwork for other institutions.