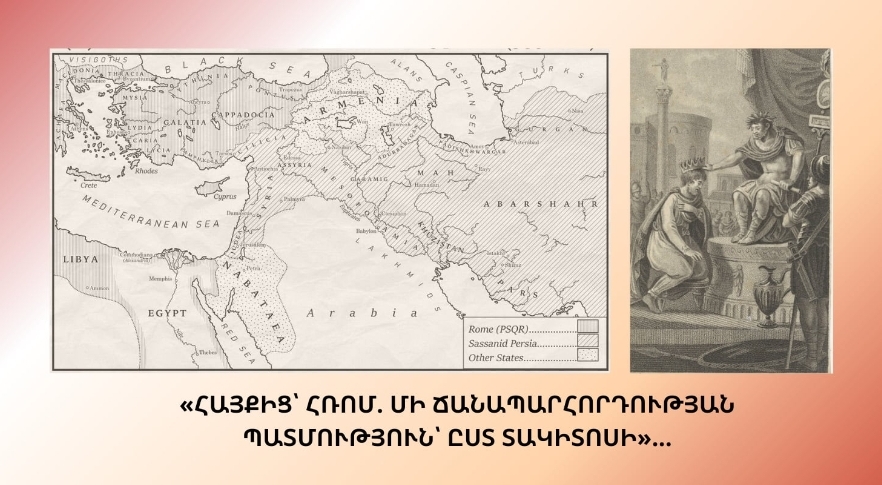

Certain episodes from the ancient history of Armenia and its relations with other empires are often known only partially, through fragmentary mentions in foreign sources, but sometimes also through detailed information.

Throughout the tumultuous centuries, profound changes in Armenia’s political situation have left their mark and inevitable consequences on the country’s history.

In the descriptions of the Roman historian Tacitus (circa 58-120 AD), the events of a period filled with conflicts 2000 years ago take shape, recently recalled in certain European countries through exhibitions dedicated to Mithraism and the mysteries of Mithraic rites, mentioning the visit of the Armenian king Tiridates I to Rome and his meeting with Nero (who reigned from 54 to 68).

Due to its geographical position, Armenia was at the center of military actions by rival powers at different times, where decisive events took place.

Here we present an interesting article from the January 1913 edition (pages 10-12) of the magazine “BAZMAVE” published in Venice, describing Tiridates’ journey to Rome, accompanied by magi and the sons of Manavaz, his solemn arrival, and the ceremonies organized.

“Fragments of Armenia”

Under this title, we periodically publish writings on the history of the Armenian nation, drawn from both ancient and modern works by foreign authors. These writings may be useful not only for historical philology but perhaps even more so for shedding light on Armenian relations with other nations and providing our young art enthusiasts with a source of inspiration for their poetic, pictorial, theatrical, musical, and other creative productions.

The following excerpt is a page from Tacitus’ “Annals.” Tacitus left his last book, the sixteenth, almost unfinished and then moved on to his “Histories.” This gap has been filled by various historians drawing from other ancient sources. This page is presented to us by Brotier, who beautifully describes the coronation of Tiridates by Nero as King of Armenia. (H. Auger)

The solemn arrival of Tiridates was a spectacle for the people, masking the embarrassment of the nobles and the Senate, but also a heavy burden for the Empire. Rome had never seen so many crowns: after a long journey, filled with superstitions and resembling a triumph, Tiridates and his wife arrived with the sons of Vologases (Vagharsh), Pakoros (Bakur), and Manavaz. Believing that actions spoke louder than words, Tiridates knelt before Nero without handing him his sword; such a gesture seemed too servile and unworthy of Arsacid nobility. Until now, nothing had violated decorum, but soon everything became mere exhibition.

Nero, who knew better how to marvel than to emulate the dignity of a barbarian, took his guests to Naples, to Puteoli, and displayed his imperial grandeur in a gladiatorial competition. The freedman Patrobius organized these games. One can get an idea of the expenses knowing that, for an entire day, only Ethiopian fighters, of both sexes, entered the amphitheater. To honor the spectacle and show his skill, Tiridates, without leaving his place, shot an arrow that, according to legend, wounded two bulls.

The spectacle in Rome was even more grandiose when Tiridates appeared there to claim the throne of Armenia. They waited for a day of good weather. The day before, the entire city was illuminated, a crowd filled the streets, and spectators crowded the balconies of houses. The people, dressed in white and crowned with laurels, filled the square. The soldiers, making their weapons and eagles gleam, formed a guard of honor. Early in the morning, Nero, dressed in his triumphal robes, went to the square with the senators and the Praetorian Guard. There, he ascended a throne near the rostrum, sat on an ivory chair, surrounded by eagles and military banners. Then Tiridates and the sons of the kings, accompanied by numerous dignitaries, arrived surrounded by troops of soldiers and paid homage to the emperor.

The clamor of the people, witnessing this unprecedented scene and recalling their ancient victories, initially caused fear in Tiridates, who remained silent and did not regain his courage even when silence was imposed on all. Perhaps he also wished to flatter the people with this false modesty to avert any danger and secure a kingdom, for he declared loudly that, although he was of Arsacid blood and brother to the kings Vologases and Pacorus, he was nevertheless a servant of Nero, whom he honored as a god, and that all his rights came from Nero’s protection, for this prince was to him both Destiny and Fortune.

Nero’s response was all the more haughty because this speech was humble: “You did well,” he said, “to come here to enjoy my presence. The rights your father could not transmit to you and that your brothers could not preserve for you, accept them only from me. I give you Armenia. Know well, and let you all remember, that I alone can give and take away kingdoms.”

Tiridates immediately approached the steps of the throne, knelt before Nero, who raised him and embraced him, and placed the crown he sought upon his head amid the loud cheers of the people, for which a former praetor translated the humble supplication of the king.

From there, they went to the Theater of Pompey. Never had gold seemed more commonplace and more devalued. The stage and all the surroundings shone with gold. Everything was covered with a vast purple curtain, at the center of which golden embroidery depicted Nero driving a chariot, surrounded by golden stars. Before sitting down, Tiridates once again paid deep homage to Nero, then took his place on his right to observe this scene where gold took on a thousand different forms. This dazzling opulence was followed by an even more sumptuous banquet. Then they returned to the theater, where Nero did not hesitate to sing like an actor, play the lyre, and drive a chariot, dressed like a charioteer among the aurigas.

In these shameful scenes, made even heavier by the poor applause of the people, Tiridates, remembering Corbulo’s military virtues, could not contain his anger and told the prince that he was very fortunate to have such a noble prisoner as Corbulo. Nero, caught up in the intoxication of his own joy, ignored this audacity from a Barbarian. There seemed to be a competition of insolence between the prince and the people. As if these ridiculous ceremonies had concluded the war in Armenia, Nero, hailed as emperor, headed to the Capitol with his laurel crown, closed the Gate of Janus, and became even more ridiculous through this imaginary victory than by performing on stage.

Having secured his crown, Tiridates knew how to benefit from the sympathy of the people and the prince. Long intoxicated by his happiness in Rome, he sought only marvels:

He found them in Tiridates’ court, who, like all Orientals, boasted of his deep knowledge of the mysteries of astrology. What made his science credible was the multitude of magi who accompanied the king.

Immediately, the Romans wished to consult their fate in the sky and the underworld. The most amusing was Nero himself, for this kind of secret particularly seduces malevolent tyrants, who are both anxious about the future and prodigal in the present, as if they could dispose of the future they fear. Nero was already enthusiastic about taking lessons.

Tiridates, proud to have such a student, began to instruct him. The master of the empire’s destiny, in disregard of Rome, gave himself up to Chaldean illusions, learned their magical rites, and progressed in the art of poison, the main branch of magic. This shameful apprenticeship revealed the falsehood and vanity of an art that could not be taught by a master who had just received a new crown, and that a pupil commanding the universe could not learn.

Nero, despite his disappointment, was no less generous. Sovereigns are all the more lavish when they feel deceived. Tiridates, who already enjoyed a daily stipend of eighty thousand gold pieces, also received a gift of one million silver drachmas. Nero also allowed him to rebuild Artaxata, which had been razed, as we have recounted. He also granted him numerous artisans, to which Tiridates added many others that he personally hired.

Thus, restoring this king to his throne cost more than dethroning other kings in the past.

Having been enriched by these gifts, Tiridates, little concerned with the superstitions of his country, sailed from Brindisi to Dyrrachium. He then crossed the cities of our Asia, admiring everywhere the empire’s sources of revenue and Nero’s senseless undertakings.

Before Tiridates entered Armenia, Corbulo, going to meet him, let the artisans who had been sent to him pass, but sent back to Rome those he had hired himself. Out of concern for Roman honor, this jealousy increased Corbulo’s renown and diminished that of the prince. Despite this, Tiridates, out of gratitude, renamed the city of Artaxata “Neronea” after restoring it.

Stay tuned for the next article, which will feature a story about a donation related to the journey mentioned…