Let’s continue the discussion from the previous post about the “Children of the Sun” by exploring the true teachings of the real Children of the Sun—according to the interpretation of the priests of the Haykian Brotherhood, who preserve the ancient solar culture of the Haykazuni lineage.

In Ghevond Alishan’s study “The Old Faith or the Pagan Religion of the Armenians,” we read: “It is more surprising and easier to believe that sun worship, more than other beliefs, has somehow deeply and lastingly taken root among our compatriots. And at various times, there have appeared ‘Children of the Sun,’ who perhaps still exist, though it is not clear to which people they belong. In the mid-11th century, Grigor Magistros mentions them by this name and considers them to be descendants of the Zandik magi. He says: ‘Some of them, having been enlightened, are sun-worshippers, whom they call the Arevordik (Children of the Sun). And many of them are found in this region (Mesopotamia), and Christians openly refer to them as such’…”

“…In the writings of authors from later centuries closer to our own, there are also mentions related to the Children of the Sun. Even today, in the regions of Mesopotamia, there are sectarians called ‘Shemsi’ (meaning ‘solar’), who follow a religion that blends elements of paganism, Christianity, and Islam.

The origin of their ethnicity is unknown, and they speak the local language.

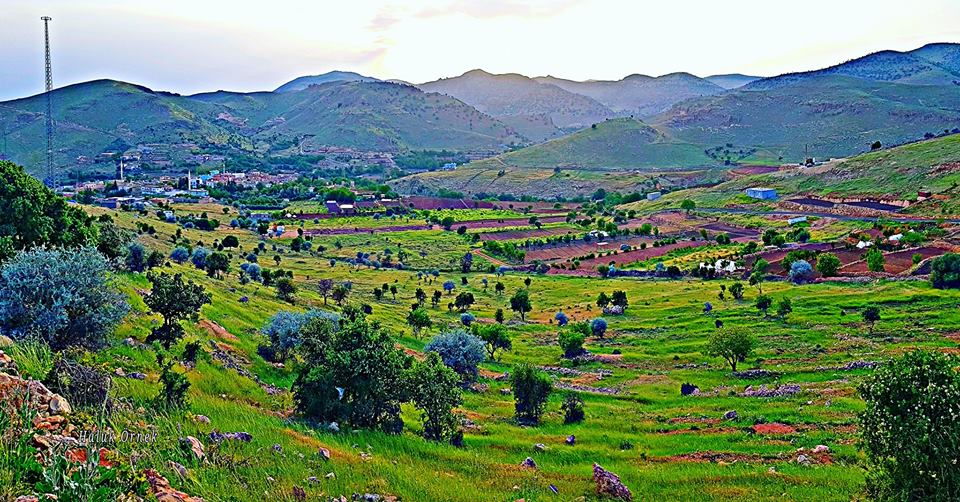

In the very land of Armenia, in the regions near Kaghzvan, one can still hear the names of the ‘Arevordi’ or ‘Artsvordi’ mountains that rise between the rivers Aras and Aratsani. In recent times, Yezidis and sun-worshippers have been found there, or at least Arevordis, who are mentioned by local geographers, among them being Texier (Texier, Asie Mineure, I, 105, 123).”

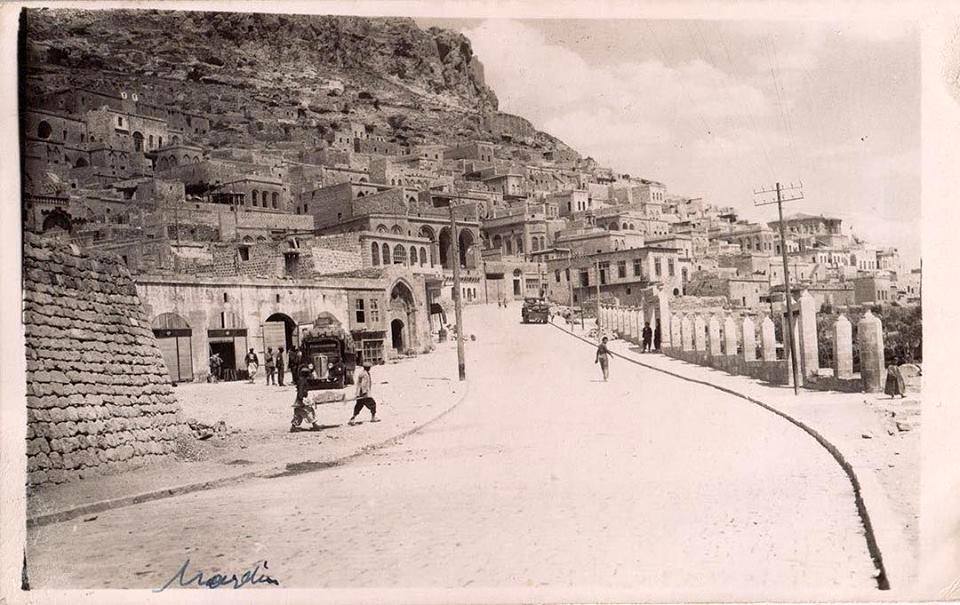

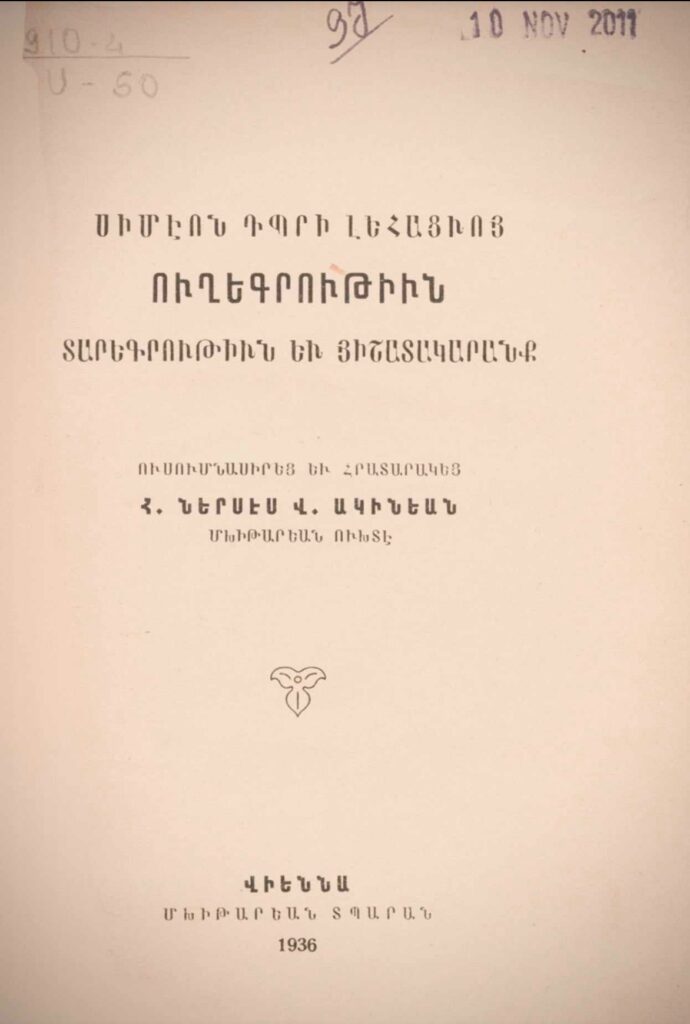

In the early 17th century, during his travels through Mardin, Simeon of Poland (Simeon Lehatsi) testifies that the “Shemsis” had a gathering place (a “prayer place”) in Mardin. They spoke Armenian, but under the threat of forced conversion, they were scattered from there—some went to Persia, while others fled to Syria, Tokat, and Marsvan (Simeon of Poland, Travelogue, p. 208, Vienna, 1936).

In the travel diaries of the 1895 expedition, French archaeologist and anthropologist Ernest Chantre (1843-1924) writes about the unique aspects of the Yezidi religion, the influences it has absorbed from other beliefs, and their morning ritual of worshipping the sun. He concludes that Zoroastrian elements have been unconsciously preserved in their practices (p. 94). Certain excerpts (translated by me) confirm the lines of medieval chroniclers:

“Some consider them to be Muslims, others Nestorians or followers of Zoroaster’s teachings. …They worship the sun as a symbol of God’s justice, the life-giving principle for humanity.”

“Like the ancient Arevordik (Children of the Sun), they worship the bard, but in extreme contradiction, they believe that by doing so, they are venerating the tree from which the wood for Jesus’ cross was made.”

“When you ask a Yezidi what his religion is, he answers that he is ‘Isavi,’ meaning that he belongs to Jesus—in short, that he is a Christian. And since they are notorious thieves and robbers, they justify their actions by saying that Jesus permitted them to steal in remembrance of the thief crucified on his right side.”

Referring to the Arévordiner mentioned by Nerses Shnorhali, who rejected the new Christian faith during its spread and preserved their own teachings, Chanteur questions Yeghiazaryan’s suggestion that this sect was likely represented by the Yazidis. He also recalls Portugalyan’s etymology of the word ‘Yazidi,’ derived from the Persian city of Yazd, where Zoroastrianism persists to this day.

The “Children of the Sun”, who have survived to this day thanks to the descendants of the Haykazuni, are Armenians who, through a special ritual known as the “Sun’s Gaze”, carry the teachings of Hayk, as explained by Kurm Mihr Haykazuni.

The confusion and ambiguity among the authors mentioned stem from the fact that, after the spread of Christianity, nations with beliefs that included elements of nature worship were often generalized as being associated with “sun worship”. The medieval manuscripts that refer to the “Children of the Sun” give us insights into the nationality of these individuals through historical accounts concerning the populations of Mesopotamia over the centuries.

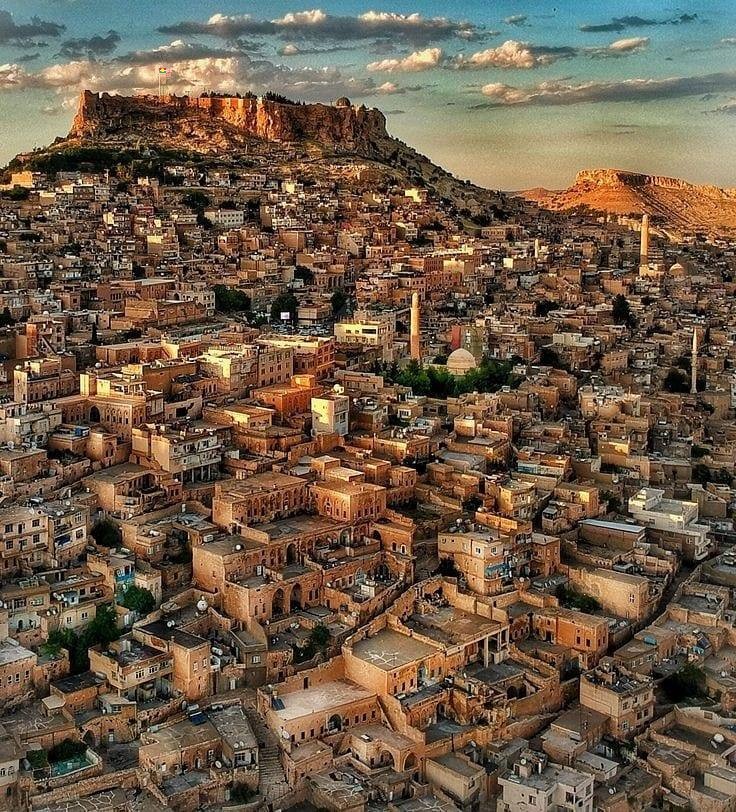

In his description of the fortified city of Mardin, located on a high, rocky mountain, and its fruitful surroundings, Ghukas Inchichian also speaks of the diverse local population: “The city’s inhabitants number about 1000, and they consist of Turks, Kurds, Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians (or Jacobites), Chaldeans, and also the Shamsiyya, which in Arabic means ‘People of the Sun,’ whom our ancestors referred to as the ‘Children of the Sun.’” (Gh. Inchichian, Geography of the Four Parts of the World: Asia, Europe, Africa, and America. Written by Father Ghukas Vardapet Inchichian of Constantinople. St. Lazarus Island, Venice, 1806, Part I, Asia, Vol. I, p. 353).

“People of the Sun, whom our ancestors called the Children of the Sun…”

“Sun worship represents the culture of Life’s Light, the quest for Wisdom and self-improvement.

The Children of the Sun are the carriers of this culture, spreading the Light and sowing Knowledge, Wisdom, and Goodness.

A Child of the Sun, in the Haykazuni worldview, is an Armenian raised with the Haykazuni philosophy, inheriting the wisdom passed down by their ancestors.

Naturally, tribes living by the lunar calendar could not be called ‘Children of the Sun,’ as noted by Kurm Mihr Haykazuni.”

Today, the priests of the Haykian Brotherhood offer precise knowledge about the ancient traditions of the Haykazuni Children of the Sun, Sun worship, and the teachings of Hayk, clarifying many questions that have remained uncertain over the centuries.

Here is a short interview with Kurm Mihr Haykazuni, providing some concise explanations.