«THE CALL»

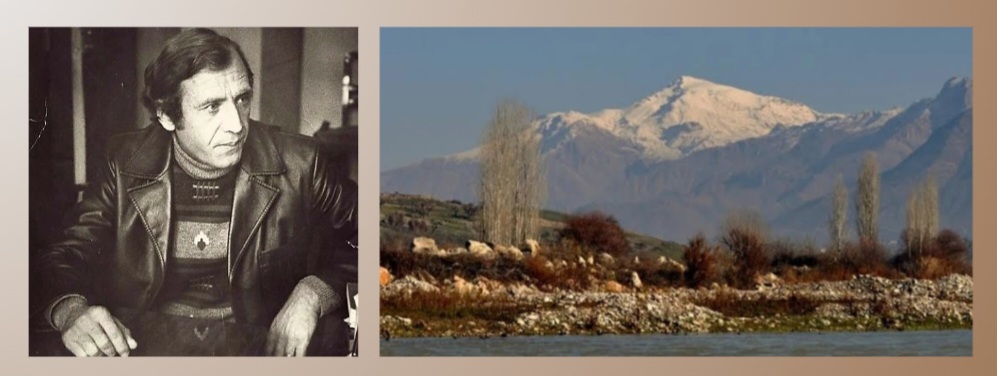

“With the cry ‘Yah, Maratuk!’ Mushegh Galshoyan gave life to each of his creations. Like the people of Sassoun, he found his muse in the sacred mountain, drawing from it the strength and resolve to complete his works with poetic mastery.

Through his words, Mushegh Galshoyan preserved the memories and tales of his homeland—the echoes of a bygone era, the untouched beauty of its landscapes, and the noble Armenians who upheld their ideals with dignity.

The lives of his characters are inseparably bound to their homeland and its nature. Even in distant lands, their hearts remain in ‘the meadows beneath Tsovasar,’ on the slopes of Maratuk, or ‘within the snow-covered peaks gazing down upon their village,’ alive with the vibrant memories of ‘ancient and modern days, moss-draped days,’ their native speech, and the unquenchable yearning for their homeland.

They entrust this to the next generation:

‘Let it be, fish! Retrace my steps along the path I walked… That path, like a thread twisted through mountains and gorges—the lost path of my battles and massacres—you will untangle and return, fish!’

Among the many expressions of endless yearning, the love call of Zoro the mountaineer stands out—a love story tragically interrupted by the Armenian Genocide, only to reignite decades later. In the ‘flowering stones of silk-shrouded Maruta Mountain,’ he unexpectedly finds ‘his little Alek, crowned with flowers, skipping from stone to stone,’ 55 years later, while seeking wine for his youngest son’s wedding.”

THE CALL

“Aleee… Ale, my dear, Aleee…”

The old man leaned on his staff and called out in a melodic tone. The lambs were scattered across the mountain slopes, but Zoro… old Zoro wasn’t a shepherd. The village didn’t have designated shepherds—each day, someone different took charge of the flock, and today was Zoro’s turn. Tall and sturdy, with thick hair, Zoro leaned on his staff, his voice rising and falling as he called:

“Aleee… Ale, my dear, Aleee…”

From dawn onward, he stood there, leaning on his staff, endlessly calling out.

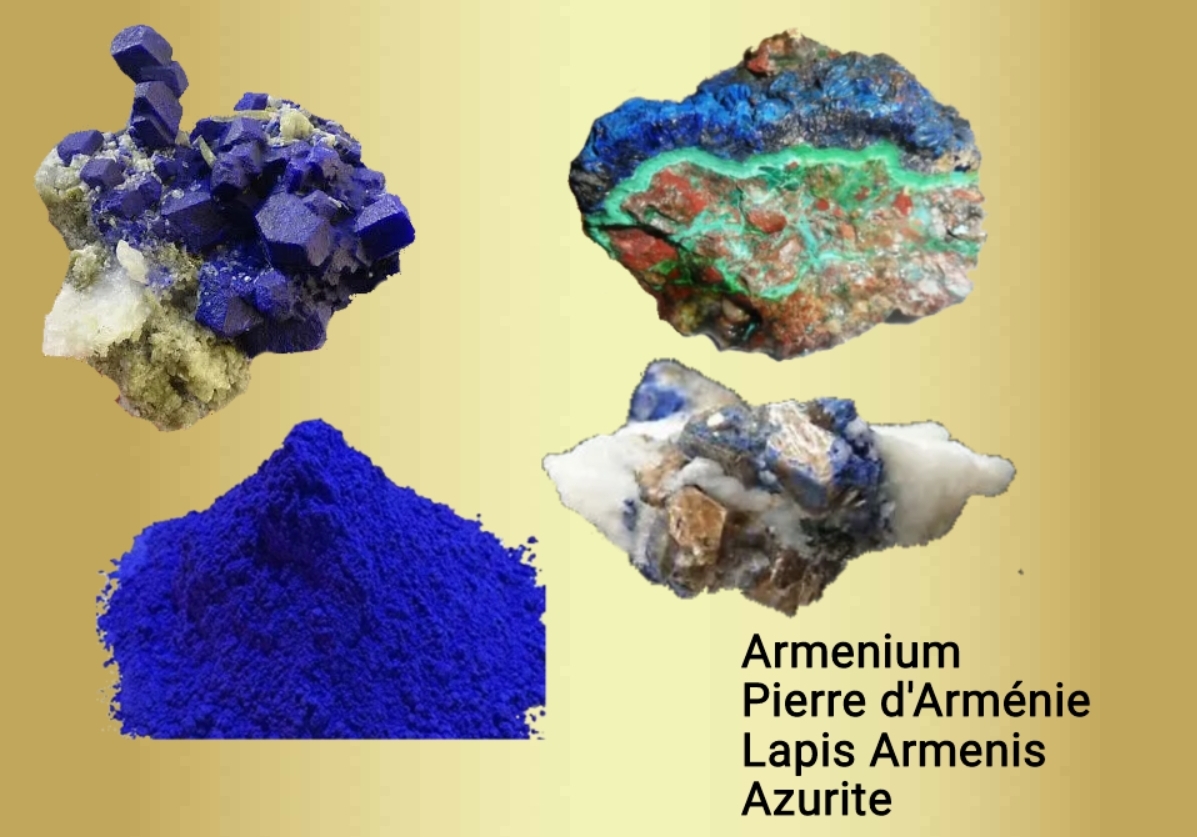

Oh, when was it? Another spring, on a morning soft and blue—a world steeped in blue. Maruta Mountain wore its blue veil; the gorges and valleys were brimming with blue skies. The villages perched on cliffs and ravines exhaled a breath of blue, and the restless winds of Talvorik poured blue mists into the gorge, bubbling and swirling… On the slopes of Maruta Mountain, lambs and kids roamed freely, discovering the world and the springtime. The young ones sniffed the rocks with their muzzles, licked the moss-covered patterns timidly, and darted away from dry thorns and reeds, scattering over the stones at the flutter of sparrows… While they explored the world and spring, Zoro—then a boy of ten or eleven—stood on a grayish-blue rock, swinging his sling furiously, whizzing it through the air, and flinging stones into the gorge.

What was fascinating was this: the stone, whistling as it flew with force, would reach the gorge, and just above it, its path would suddenly break. Like a bird struck mid-flight, the stone would flutter and fall into the depths of the ravine.

A group of girls picking greens moved up the hill like a colorful wave. Among them was little Alek, about seven or eight years old, with shiny black eyes, two thin braids, barefoot, wearing a pretty apron, full of energy, like a little flame. Like one of their playful goats, like Zoro’s lively lambs with white-tipped ears, she jumped from stone to stone…

Alek… She had made a crown of flowers and placed it on her head… Alek… a bouquet of colorful blossoms swaying with the breeze…

Little Alek… And Zoro suddenly realized—she was his Alek, and no one else’s. She was his Alek, and she was real.

This blue world was his—the fields at sunrise, the silk-covered Maruta Mountain, the fragment of white cloud resting like light on the Monastery of the Virgin, the noisy Talvorik River, the scattered smoke above the village, the lively lambs and goats, the sun, the sky, the flowering rocks, the boulder where he stood spinning his sling with force—whizz, whizz, whizz! That wild sling was his, Alek… the little Alek with a crown of flowers, hopping from stone to stone, was his and his alone.

2

“Aleee… Ale, my dear, Aleee…” The old man, leaning on his staff, called out with a melodic voice.

That spring morning felt so beautiful and blue to him because he knew darkness would follow…

The shepherd boy, grazing his lambs in the green fields, had noticed little Alek that morning, had found her, because he was meant to lose her…

And he saw her again fifty-five years later…

When Zoro was planning his youngest son’s wedding, he decided to personally bring the wine, and it had to be from the Ararat Plain. For his other sons’ weddings, he had hosted small, modest celebrations. But now, things were different—he could afford a proper feast, with an abundant table, fine wine, and the best Ararat Plain’s vineyards had to offer. No matter how much his older sons tried to convince him to get factory wine, Zoro refused. It had to come from the Ararat Plain, and he had to choose it himself.

That morning, he got into his son’s car and they drove to the plain. Village after village, Zoro tasted wine but found nothing he liked. By evening, frustrated, his son was speeding down the road when Zoro suddenly grabbed the wheel, insisting they take a small side road. The car swerved and ended up in some bushes. The damage was minor, but his son was livid.

“Relax,” Zoro told him. “This happened for a reason.”

“This village feels right,” he added.

At the village center, they met locals. Everyone had wine and invited them to their cellars, but Zoro approached a quiet man standing apart.

“Why wouldn’t I have wine?” the man said. “Anyone with a vineyard has wine.”

“I’ll take your wine for my son’s wedding,” Zoro declared. “Let’s go to your house.”

The house was warm and welcoming, with vines and peppers hanging from the trees. An elderly woman was threading the peppers when Zoro commented on the man’s fine home.

“It’s your wife?” he asked.

“Yes. She’s from your homeland.”

At this, Zoro turned to the old woman, asking about her village.

“Sarekin,” she said. At that name, Zoro froze.

“Sarekin?” he repeated, stepping closer, his voice trembling.

The woman’s eyes were tired yet lively. Zoro dropped his gaze, whispered her name, “Alek,” so softly she didn’t hear. Then, straightening his posture as if reclaiming his strength, he looked beyond her toward the distant mountains. With all his breath, he called out, “Alek! Alek!”

The old woman, frazzled and unsure, studied Zoro as he stood there, his half-closed, hazy eyes lost in the act of softly repeating her name. His words carried a distant warmth, and she felt a sudden urge to cry.

Zoro turned his unfocused gaze to her and whispered again,

“It’s me, Zoro… Alek.”

He took her hands in his and pressed them gently to his forehead before bringing them to his lips.

Startled, the old woman remembered the customs of their homeland—by tradition, a woman should kiss a man’s hand. She quickly bent down and kissed Zoro’s. Tears—forgotten for so long—began streaming down, and their refuge became Zoro’s hands.

What happened next was almost playful: they started reaching for each other’s hands, trying to kiss them. The red pepper garland hanging from the old woman’s arm brushed against their faces, tickling their eyes. Alek sneezed, interrupting the flow of her soft tears. Though she found solace in weeping, she rubbed her eyes, and her warm, clear tears turned blurry and stung beneath her lids.

Standing face-to-face, the two aging figures rubbed their irritated eyes with their fists, looking at each other with unfocused gazes.

“Dad, we’re running late,” the son said gently.

Zoro snapped back to the moment. He glanced at his son, then at the host, before turning to Alek and nodding slightly.

“Alek…” he muttered. He wanted to say more but instead turned to the host. “So, she is your wife. May you live happily together,” he said quickly before adding, “Where’s the wine?”

In the cellar, the host filled a copper ladle with wine and handed it to Zoro to taste. Zoro drank it in one long gulp, emptying it with satisfaction.

“Ahhh!” he sighed, wiping his mustache with his hand. “That hit the spot… I’ve never tasted wine this sweet before, Alek. It’s delicious.”

Lowering his head, Zoro’s gaze shifted subtly to the old woman standing quietly in the corner of the cellar. Turning to his son, he said:

“Now do you see, son, why we’ve been driving from village to village, all day, leaving each one empty-handed? Now do you understand? This is the wine I was looking for—this one, and no other. Fill it up!”

“How much, for how many jars?” the host asked.

“I’ll take the whole jar,” Zoro said firmly, his voice unyielding. “Fill it up—no need to bargain. This wine is beyond price,” he said, protesting. “Its worth is in the taste itself, Alek. Fill it!”

The host tried to take back the ladle, but Zoro refused.

“Fill it with something else—this one is mine.”

The host repeatedly explained that drinking standing up wasn’t proper. There was a table, a house, and they could sit down later to drink together and get properly acquainted, especially since they were old neighbors and fellow villagers. But Zoro ignored him. His son tried to nudge him to comply, and Alek chimed in as well, but Zoro insisted on drinking right there, straight from the copper ladle, directly from the jar.

Left with no choice, the old woman brought bread and other snacks, setting them up nearby, but Zoro didn’t touch the food. He leaned against the wall near the wine jar, pouring and drinking, pouring again and finishing every drop. He wiped his mustache, clenched his fist, and muttered softly, “Alek…”

The old woman, now sitting at her makeshift table, seemed lost in thought. Earlier, she had been lively and cheerful when Zoro arrived, but now she appeared small and hunched—truly an old woman, caught in a trance. Her eyes stung, and she felt the lingering urge to cry, the sweetness of her interrupted tears welling up again.

“We’ve seen your husband, Alek. What else do you have?” Zoro asked.

“Thanks to God, I have sons, Brother Zoro,” she replied, trying to hold back her tears. “I have daughters-in-law, married daughters, grandchildren. And you, Brother Zoro?”

“Thanks to God, I have sons too, Alek. Daughters-in-law, married daughters, grandchildren,” Zoro said. Then, filling the ladle again, he added, “And this wine—this sweet wine, for the happiness of my youngest son, for his wedding, Alek. Ah, Alek, my soul!”

And he started singing.

The host, leaning over the jar, glanced at Zoro and smiled, clearly pleased with how strong his wine was.

“What amazing wine this is, Alek,” Zoro said, pausing mid-song. “All this time, such sweet wine was here, and I had no idea! Ah, Alek!”

Then he continued his song.

The host and Zoro’s son finished measuring and paying for the wine. Zoro was still singing. The host lit a cigarette and sat next to his wife. Zoro’s son loaded the barrels and jars into the vehicle, then returned to the cellar to see Zoro still singing, completely absorbed in his own world.

By then, the copper ladle was empty. Somehow, during his last song, Zoro had spilled the wine and unknowingly drenched himself from head to toe.

“Ah, Alek…”

Just as he had begun, so he finished his song, opening his eyes but seeing no one—not the dazed Alek, nor the chuckling host, nor even his son standing nearby, who took the copper ladle from his hands and slipped an arm around him.

“Let’s go, father.”

Zoro shifted his arm and pressed firmly against the wall.

“By the oath of Maratuk, my feet won’t leave this place! Alek…”

The host suggested they head to the house so Zoro could lie down and rest.

“Rest?” Zoro scoffed. “Do you think sleep will come to these eyes of mine now?”

He rubbed his eyes with clenched fists.

“Alek,” he called out, “where have you gone?”

Once more, his son tried to pull him away, but Zoro shoved him back, swore at him, and even insulted the host. Like a stubborn child clinging to the wall, he refused to move and kept calling out,

“Alek…”

The host finally spoke up, pointedly:

“Are you driving me out of my own house?”

Zoro didn’t respond, unwilling to release his grip on the wall.

“Bread and wine, Lord of All Life, I’ll smash your jars and barrels to pieces if you send me away! Alek…”

In the end, the son and the host had no choice but to drag him away. Zoro, still calling for Alek, searched for her with his eyes as they pulled him out of the cellar, unseeing, unhearing, his cries growing fainter as they moved.

The old woman, trembling and overwhelmed, collapsed to her knees and wept openly. Outside, Zoro’s voice echoed:

“Alek…”

No one had ever called her name like that—so warmly, so earnestly, so full of longing, like a prayer, like a song, like the distant echo of the mountains.

“Alek…” The call faded further and further into the distance.

Zoro called out in the dark street, and as they left the village, it was the same, continuing until he fell asleep.

3

Even in his sleep, his lips trembled,

“Alek…

Alek, my soul, Alek…”

The old man, leaning on his cane, was calling out, singing the name. A boy and a girl were climbing the hill. They were Zoro’s grandchildren, his son’s children, the same ones for whom the wedding wine had come from Alek’s house.

After the wedding, Zoro went to the fields a few more times to see Alek, but then winter came, and then spring. With all the work and daily life, he sometimes thought about going back to the field, but something always stopped him. And so the years passed.

Six years.

But today, Zoro felt completely different.

He had taken care of the lambs, his place on the mountain behind the village, his life. In front of him were the blue valleys and gorges, the Ararat plain with a thick veil of mist, and the silver line of the Araks River. Below, the tents were stirring in the wind, and in the distance, the rugged Armenian mountains stood tall. But for Zoro, there was another spring morning, one filled with the promise of new life. A world where lambs and goats grazed together, where a young shepherd tended them, and where girls gathered vegetables. There was also a small girl with a flower crown, hopping around like a bird…

“Alek,” Zoro called, looking toward the horizon.

“Alek, my soul, Alek…”

It was then that he noticed his grandchildren, who were next to him, the little girl rubbing against his legs like a kitten.

“But where are the lambs, papa?”

“The lambs?” Zoro took a moment to respond.

“The lambs?” His eyes searched the surroundings, lost in thought.

“What could happen to the lambs, my dear?”

His knees ached, and it felt as if the ground was pulling him down. With a groan, he sat down, but his gaze lingered on the horizon, while his thoughts replayed the same refrain.

“Let’s eat!” the little girl exclaimed, eagerly unwrapping the bundle. “We’ll eat everything, Papa!”

“A glass of wine would do me good,” Zoro thought and, without hesitation, decided: “I’ll get up and visit Ale.”

“Where are the lambs, Papa?”

“They’re not here?” Zoro pushed himself up with the help of his staff. “I’ll go to Ale and see.”

“The lambs are… over there,” he said vaguely, pointing with his stick. “Go gather them with your sister, eat some bread. I’ll head to the village and come back.”

On his way home, Zoro couldn’t stop reproaching himself for not visiting Ale all this time. He wondered—why hadn’t he gone? Was it a lack of time? Weakness in his body? Lack of means? No road or vehicle? Why hadn’t he gone, why had he delayed the visit when it first came to mind?

And somehow, his wife became the scapegoat. By the time he stepped into the house, he was already angry with her.

- “The bread in your hand is cursed.”

- The moment he stepped through the door, the fight erupted.

- “It’s cursed,” Zoro repeated. “With your right hand, you fed me bread, and with your left, you snatched away my soul,” he said. “You’ve taken my soul and forced it into my mouth. I ought to break this stick over your head!”

- Gripping the stick tightly, he struck his own head instead. He hit himself and then had a sudden realization:

- “God has destroyed the sanity in my mind. What’s the point of visiting Ale now? What’s the point? I’ll go, take her, and bring her back.”

- The old woman stood still, shocked and bewildered.

- “You’re the reason I’m suffering!” Zoro shouted.

- “They were right when they said an Armenian’s last bit of wisdom is in his head… That day, the day of the wine, I should have brought Ale home!”

- “The reason for my torment is your children—your daughters and your sons.”

- “That very day, I should have put Ale in the car and brought her here.” He thought about how his son would have stood in his way and refused to let it happen.

- “My tormentor is your middle son, your youngest son. And I live under their rule… This house feels like a prison; I can’t breathe here. I’m leaving.”

- Zoro made up his mind then and there:

- “Tonight, I’ll prepare that old shed. Tomorrow morning, I’ll bring Ale home.”

- “Let heaven and earth collide, but I’ll leave, and I’ll leave!” Zoro insisted.

- “If it can’t be done kindly, I’ll take her by force.”

- “Enough! Whether it’s peaceful or not, I’ll leave.”

- And under the astonished, confused gaze of the old woman, Zoro stormed out.

- Behind the new house stood a small shed—the old house, its door tied shut with wire. Inside were forgotten items: a worn-out cradle, a burnt stove, a plow, a scythe, a sickle…

- Zoro picked a stove that still worked, two chairs, and carried the rest outside, arranging it behind the shed. He cleaned the walls and ceiling, reinforced the door, and prepared the old house.

- By evening, when his sons gathered, they found their father had already set up his bed, brought dishes, a sack of flour… He had created a separate home and was sitting at the door, calmly smoking.

- The sons were frantic—who had offended their father? They questioned each other, interrogated their mother, and even asked Zoro himself—what had happened? But Zoro dismissed them with a few words:

- “The world has wronged Zoro… Everyone in this world has insulted Zoro. And Zoro is angry with the world and… only Ale… In this entire world, only Ale matters,” and he would leave.

- No matter what they said or did, Zoro didn’t return to the house. He refused to live under the roof of either of his married sons.

- His decision was final, unshakable.

4

The next afternoon, Zoro arrived at the village in the fields. He wandered in front of Ale’s house several times, hoping to catch her outside. He paced back and forth, stood under the mulberry tree by her window, knocked a few times, and hid behind the trunk, waiting for her to appear at the window. If she did, he’d wave and call her over. But no matter how many times he knocked and waited, Ale didn’t come. The street was quiet except for a few children playing—it was spring, and everyone was busy with work. - Finally, Zoro had to enter the yard. The moment he stepped inside, he saw Ale. She was near the same apricot tree where he’d seen her the day they carried the wine (she’d been picking red chili peppers then). Now, vegetables surrounded the tree, and Ale was working the soil. She looked so small. Sitting on a low mound, she leaned to the side, lightly tilling the ground, her movements casual, almost absentminded. To Zoro, it seemed like she was humming an old song, one from their homeland, maybe the same one she’d sung on the wine-carrying day. He couldn’t hear anything, but he imagined it.

- Hearing his voice, the old woman turned quickly, a motion that seemed uncharacteristic for someone her age.

- “My Ale, my dear!”

- Zoro leaned his staff against the apricot tree and held her hands.

- “It’s good to see you… So small you’ve become… like little Ale.”

- He gestured toward the mountains.

- “Like little Ale. Do you remember? It feels like yesterday. You had a wreath of flowers on your head, jumping like a little goat from stone to stone. Do you remember? That was the day my heart began to race…”

- Just like before, Zoro’s gaze drifted toward the distant mountains, while Ale stood before him, small and frail, her eyes half-closed, with a look of someone who had lived through much.

- “Let’s go inside, brother Zoro.”

- “No, not the house, my dear,” Zoro said with energy. “There’s a young apple tree in the orchard. Let’s go there.”

- He asked for wine in a copper bowl, took his staff, and sat under the apple tree. Resting his hat on his knee, he looked toward the mountains.

- “My cause is just, and Maratuk is my witness.”

- “My cause is just, Ale,” Zoro said, accepting the wine. “And Maratuk is my helper.” He drank, straightened up, and said:

- “Now, ask why Zoro has come.”

- “We’re old friends, brother Zoro,” Ale said. “We’re from the same homeland. Visiting is natural.”

- “Is that all, Ale?” Zoro replied. “I told you something earlier… That day, just like today, my heart was moved because of you, Ale.”

- The old woman looked at him silently, unsure.

- “Should I bring bread, brother Zoro?”

- “No bread. Just wine.”

- “Oh Maratuk,” Zoro thought. “The fire your holy hand kindled—may your hand now calm it.”

- “That day…” Zoro continued, “that spring day, when Maruta’s high monastery filled my heart with your love, Ale, you were just this tall.” He gestured to a short height. “Did you know? That was when I realized that Ale—the barefoot, dew-covered Ale, the Ale with the flower crown—was my Ale. Mine and no one else’s. Did you know? That day, Maratuk gave us love, but then the lawless came and tore it away… Wolves attacked the innocent, leaving only destruction and darkness. The sun was darkened, Ale, and you and I lost each other… Is my word true, my dear?”

- Are you speaking about the massacre, Brother Zoro?

- Yes, the massacre… and love, Ale.

- The old man took another sip of wine, lit a cigarette, and waited. Ale stayed silent, her shoulders hunched, her fingers busy with the greens around her.

- You’re still my Ale, he murmured. That day isn’t gone, Ale. That spring day, so vivid, is still here before my eyes. The lambs will frolic at the foot of Maruta, and you…

- Zoro recounted the memory again, the colorful spring morning that had lingered in his mind like velvet.

- Maratuk blessed my love that day, and from then until now, it’s been my sacred burden, Ale. Stand up, gird yourself, and let’s go, my dear.

- Go where? Ale asked, confused.

- You ask where? Ale, who do you think I’ve been talking about all this time? Stand up, and let’s return to our village. I’ve been apart from my people for so long. However many days we have left, let’s spend them together. Let Maratuk decide our fate.

- Are you crazy? Ale muttered under her breath, hiding a smile and trying to take the wine away.

- It’s not the wine, Ale! The wine is innocent—it’s this! Zoro tapped his chest. This is for you. Who was that story for if not you? Why did that morning happen if not for us to reunite? Was it all for nothing? If we weren’t meant to come together, why was I made to find you that day, only to lose you by evening? Was it a dream? No, Ale, that morning was real. It still is.

- Get up, gird yourself, and let’s go, he said again.

- Brother Zoro, I swear, you’ve gone mad, Ale said, exasperated.

- Mad or not, I’ll elope with you, Zoro said, striking the ground.

- Ale laughed softly.

- How will you manage that, Brother Zoro?

- You’re so tiny; I’ll toss you into a sack. Getting out of this village won’t be a problem. The world will keep turning, but Ale will still be mine. I’ll make it happen.

- A voice called from the yard, pulling Ale back to reality.

- That’s my husband, she said, standing up quickly.

- He’s a good man, Ale, but I’ll elope with you. Night will fall, and I’ll come back for you, Zoro said, tugging at her skirt. Just keep quiet and don’t make a sound.

Cheers! - Zoro drank two quick glasses of wine and turned his focus to the young man.

- The young man’s eyes sparkled with joy, as if a song were dancing in them. Yes, Zoro thought, those with such lively eyes often have voices that can carry a tune.

- Do you know how to sing a song?

- I do, the young man replied happily.

- Then sing a song for your uncle’s glass.

- As the young man sang, Zoro drank again, but he noticed his vision starting to blur. So soon? He had barely had a few small glasses. That was a sign to stop. Zoro wasn’t here to drink. Let the host and his sons drink. Zoro had something else in mind. Where is Ale?

- The old woman moved in and out of the room in small, careful steps, a faint, secret smile playing on her lips.

- Good for you, lad!

- Zoro raised his glass again, hesitated—should he drink or not?—but drank it anyway.

- Now listen to me. I’ll sing a song for you.

- He closed his eyes, swayed slightly with his shoulders and torso, and then, with a deep, raspy cry, began to sing: Heeei-aahhh!

- Raising his hand high, he poured himself into the song. His aged, trembling voice carried a tune of nature—of mountains with colorful flowers, paths winding upward, and carts climbing toward the heavens. His gestures were sweeping and dramatic, even knocking over a bottle. The young bride scooted away to give him space.

- The song was about shepherds in green fields and girls with bright aprons full of vegetables.

- It was a song of nature and love.

- When Zoro finished, he continued to sway, as if still caught in the rhythm. He leaned forward and called softly: Aleee!

- Was it part of the song? Or was he calling her name? The host wasn’t sure.

- Ale had stopped what she was doing and sat quietly at the table’s edge. Her earlier liveliness was gone, and her faint smile had faded. Now, she looked at her old friend with a mixture of sadness and tenderness.

- Aleee! Zoro looked out the window at the sun setting behind the mountains.

- There should be no sunsets, he murmured. No evenings or nights, no summers or winters—just a spring that lasts forever. And we should never grow old, Ale. Let children stay children. Let me sit on that rock, and you rest among the flowers, crowned with blossoms… Always crowned with flowers, Ale.

- Mother, he’s here for you, the youngest son said.

- Everyone sat in silence, listening to Zoro’s words. The youngest son, deeply moved, said again:

- Uncle Zoro came for you, Mom… Sit by him.

- The old woman hesitated but allowed her son to help her sit next to Zoro.

- Oh, Maratuk!

- Zoro stood, embracing Ale. She pressed her face against his chest, and he leaned his head to touch her hair. Looking out the window, he softly sang:

- Aleee… Ale, my soul, Aleee…