“Cheto – Peto”, “The Gossip of Kajet Women”, “The Punishment of Kajet”

Culture, particularly folklore, serves as the finest reflection of a nation’s worldview and core values. As Hovhannes Tumanyan insightfully remarked, folklore provides the foundation for nearly all arts, especially the literary ones.

Through the relentless efforts of folklorists, we’ve preserved extraordinary examples of Armenia’s rich and diverse folklore, spanning multiple genres. These epics and lyrical works are frequently complemented by humorous and witty anecdotes, bringing the vibrant spirit and echoes of distant eras into the cultural treasury of the Armenian people.

The Armenians of Shatakh in the Van province were heroic participants in the self-defense battles of 1915, bravely fighting for 42 days with unyielding resolve, joined by women and children.

The “people of the land,” with their “songs and tales,” shared stories from ancient times. Among them was Rasho, one of the “crooked men of Kajet,” who sometimes recited slowly, other times with passion and a commanding voice. With remarkable speed and an air of ceremony, he would “emphasize the key points and deliver two dozen lines,” as vividly described by K. Melik-Ohanjanyan.

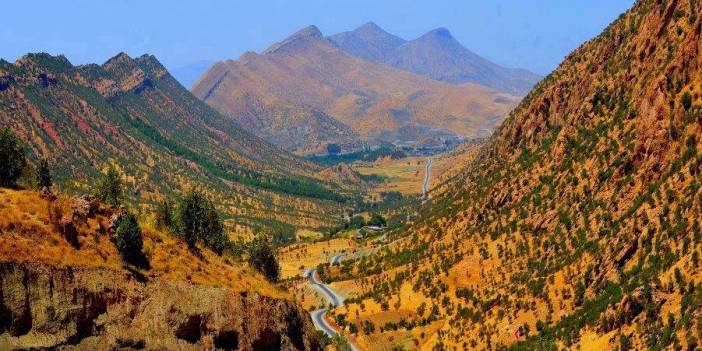

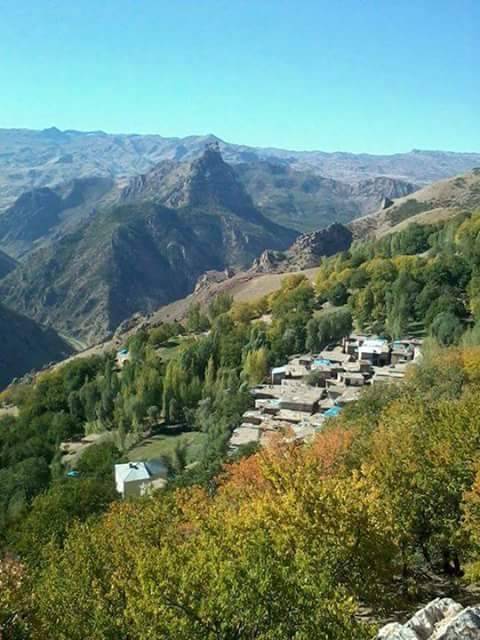

The village of Kajet, nestled in the Shatakh district and blessed with pure, abundant springs, had a legend about its water — it was said to “drive people mad.” Unsurprisingly, many humorous and satirical tales were spun about its quirky inhabitants. Here’s one such story from Anushavan Devkantsi’s works:

Cjeto-Peto

Res Ako was busy organizing his eldest son’s wedding. Everything was ready: food, drinks, and music. All that was left was to invite the relatives and friends — with all the respect and ceremony expected in Armenian traditions, even in Kajet, the “village of the crooked.”

Res called over his son and said:

“Go to the village square and see which of our relatives and friends are there. Invite them all and tell them we’re going to eat, drink, and party until Kajet shakes with joy!”

The son got ready to leave, but Res stopped him and added:

“Oh, and if you see Uncle Cjeto-Peto in the square, just give him a half-hearted invite. If he comes, fine; if he doesn’t, even better.”

The son reached the square and saw Cjeto-Peto sitting on the tallest stone, chatting with Kajet’s elders and relatives, young and old. Res’s son respectfully invited everyone present, naming them one by one on his father’s behalf. Finally, he approached Uncle Cjeto-Peto and said:

“Uncle Peto, you’re invited to our house… my father’s calling you too.”

Cjeto-Peto gave a sly look to the crowd, turned to the young man, and asked:

“Your father’s calling me, got it… but why are you covering half your mouth with your hand while inviting me?”

The groom-to-be replied with a grin:

“My father told me to invite you with half a mouth, so I did!”

The Gossip Chain of Kajet

One day, Granny Shusho showed up late to church. She shuffled in quietly, covering her nose and mouth with her headscarf, and stood near Godmother Khandut.

Godmother Khandut leaned over and whispered:

“Granny Shusho, what kept you so long?”

“Godmother Khandut,” Granny Shusho whispered back, “the barn manger collapsed, so I was helping my husband fix it.”

Godmother Khandut turned to Godmother Iskuhi and whispered:

“The manger collapsed. That’s why she was late.”

Godmother Iskuhi leaned toward Granny Deghdzuni and whispered:

“They’re saying the manger collapsed.”

By the time church ended, the women of Kajet, huddled close together, shuffled out and dispersed to their homes. A couple of hours later, the whole village was abuzz with the news:

“Did you hear? They’re saying the city of Mosul has been completely destroyed by an earthquake!”

The women of Kajet, along with Granny Shusho and Godmother Khandut, slapped their knees in despair and cried out:

“Oh no, such a shame! What a terrible loss! How could the great city of Mosul have crumbled?”

Kajet’s Reckoning

In Kajet, the villagers had more to worry about than just tax collectors—they had crows. The Kajet people despised these noisy birds. Every time the crows circled above, screeching and cawing, some disaster would follow. One man’s ox would fall into a rutabaga pit, another would get his hand stuck in a jar, someone else would pull a muscle from coughing too hard, and a few unfortunate souls would trip over their feet in their new red shoes. Then there were those who mistook chili peppers for apples.

Calamities were as constant in Kajet as the ominous cawing of the crows. Many believed the crows were to blame for it all.

One day, the villagers had enough. They gathered and decided to catch at least one crow and make it pay.

With tools in hand—axes, hammers, rakes, sickles—they stormed after a flock of crows, yelling and creating chaos, determined to trap one.

Splpoch, the village boy, brought his slingshot. He loaded it with a stone, took aim, and fired. Thwack! One crow fell straight to the ground.

Shouts of triumph erupted. They grabbed the bird.

“What now?” someone asked.

To the church they went, where the priest performed a solemn ritual, cursing the crow and all its kind.

“Let’s break its neck!” someone suggested.

“No, break its legs!” another cried.

As they debated, the crow regained consciousness. It flapped its wings and let out a defiant Caw! But the Kajet folk weren’t about to let it go after all the effort they’d put in.

“Throw it in the barn!” someone shouted.

“No, lock it in the granary!” another added.

“Burn it along with the barn!” yelled a third.

Finally, Res Ako, the village elder, raised his hand for silence.

“According to tradition,” he declared, “the crow must be rolled down the cliff in a churn.”

“Yes, that’s the way!” the villagers cried.

They stuffed the crow into a giant churn, sealing it with a rutabaga. With great ceremony—crosses, incense, and the music of zurnas—they rolled the churn off the cliff.

Boom… bang… crash! The churn smashed against the rocks as it fell, and the mountains echoed with the villagers’ cheers.

Then suddenly, a sound broke through:

Caw… caw!

At the bottom of the cliff, the churn lay shattered, the rutabaga lid in pieces. The crow, very much alive, flapped its wings and flew off, cawing triumphantly.

The Kajet folk stood in stunned silence.

But they weren’t ones to give up easily.

“Curse you!” the priest yelled after the bird. “You didn’t die, but at least we scared you, didn’t we?”

Kajet (a village referenced in Armenian folklore)