Studies on the initial stages of Christian community formation in Armenia and beyond offer a glimpse into that era.

“An ancient tradition of the Eastern Mediterranean, later formalized as doctrine, narrates the story of Christ-God, who took human form, suffered, and was crucified for the salvation of mankind. This doctrine provided a sense of comfort and solace. But when the apostles who were fishermen were succeeded by popes and patriarchs wielding both pastoral staff and royal scepter, faith turned into a nightmare.

These early Christians were, in fact, barbarians themselves: they first tortured their prophet, crucified him, and then knelt before his mutilated body. This faith was adopted by anonymous people, Jews of the diaspora, and Assyrians.

They were homeless and without a homeland. They lived in ports, under sacks of goods being unloaded, in the slums of Rome. Dirty and in tatters, they crowded the markets and public squares, eating rotten bananas and oranges, offering their services to passersby. Mary’s actions are dubious, Paul was a criminal, Magdalene a prostitute, and Judas shared the same table as the Son of God.

And the question remains: who was the greater barbarian, the Christian Alaric or Attila, who had no faith but still brought destruction to Rome alongside him?

Christianity is like the sacred river of Egypt, depositing mud along its banks. It overflowed, submerging an entire civilization under the mud it carried, creating fertile soil for new growth.”

“… The conversion began, and in the course of this conversion, an entire civilization was trampled.

Gregory the Parthian urges the king to demolish, destroy, and obliterate everything pagan, to eliminate any temptation so that no obstacles remain in the path…

… For the sake of common peace.

It was in this spirit that all massacres and the St. Bartholomew’s nights were born. The king complied with the Caesarian apostle’s request. He ordered that the old gods, once venerated by his ancestors and himself, be declared false gods and erased from memory.”

“… When faith merges with power, crime surfaces.

And it surfaced: in Artashat and later in Yeriza, the temples of the Great Anahit were torn down and burned.”

“And the apostle bearing the cross appeared” (…) “he rose, dismantled, and brought down all the temple structures.”

“The historian then adds, with satisfaction: ‘All this was carried out by the will of the merciful God through the hands of Gregory.’ And Gregory the Parthian, who destroyed ancient Armenian civilization by fire, was called ‘the Illuminator.’”

After the above excerpts from the book Mashtots by the distinguished linguist, historian, and doctor of philology Artashes Martirosyan, let us examine some passages from the article Assyrian Sources on the Armenian Church by Dr. Hayk Melkonyan:

“It has been determined that in these early Christian communities, representatives of various nations gathered, which meant that these organizations lacked a national character. Their unifying strength was this progressive ideology that called upon the oppressed, the despised, the abandoned, and the dissatisfied in society to unite.”

(…)

“Before addressing these traditions (later accounts, various ‘lives of saints,’ etc., K.A.), one should consult the work Jewish Antiquities by the 1st-century Jewish historian Flavius Josephus, which contains interesting information regarding the early Jewish preachers. According to this historian, around the mid-1st century AD, Jewish preachers Ananias and Eleazar of Galilee were spreading the Jewish religion in Charax-Spasini and Adiabene.”

(…)

“And when the question of Izates’ circumcision (son of Monobazus, king of Adiabene, K.A.) arose, Ananias believed that such a rite was unnecessary to become an adherent of the new religion.”

(…)

“We believe that this account from Josephus refers to Christianity, as in its early days, this new doctrine was known as the ‘Jewish religion’ outside of Judea. Furthermore, it is well documented that Mosaicism was a religion that strictly pertained to the Jewish nation and, by its principles, sought the salvation of the Jewish people alone, making it understandable that such a religion would not be preached among non-Jews.”

To disseminate a foreign religion, special schools were established in Armenia, where education was provided in three languages: Greek, Syriac, and Persian. Students were chosen from each province and region. According to Agathangelos, groups of children were forced to leave their native places to receive schooling.

The first educators in these schools were Greek and Syriac missionaries who had accompanied Gregory the Illuminator to Armenia. “He found many brothers, whom he convinced to join him to be ordained as priests in his country, gathering numerous groups, and he brought them with him,” Agathangelos recounts. “Later, the successors of the Illuminator emulated their ancestor. Armenia became crowded with foreign missionaries, who proved to be more of a burden than a boon,” writes Bishop Vahan Ter-Yan.

For many generations, the Haykazunis, as noble and honorable Children of the Sun, stood in defense of their ancestors against the unimaginable pressures and persecutions of outsiders, preserving and passing down the doctrine of Hayk, along with Armenian traditions and values, from generation to generation.

In the writings of various periods and in medieval literature, there are mentions of the Children of the Sun, often distorted by the circumstances of the time and by ignorance.

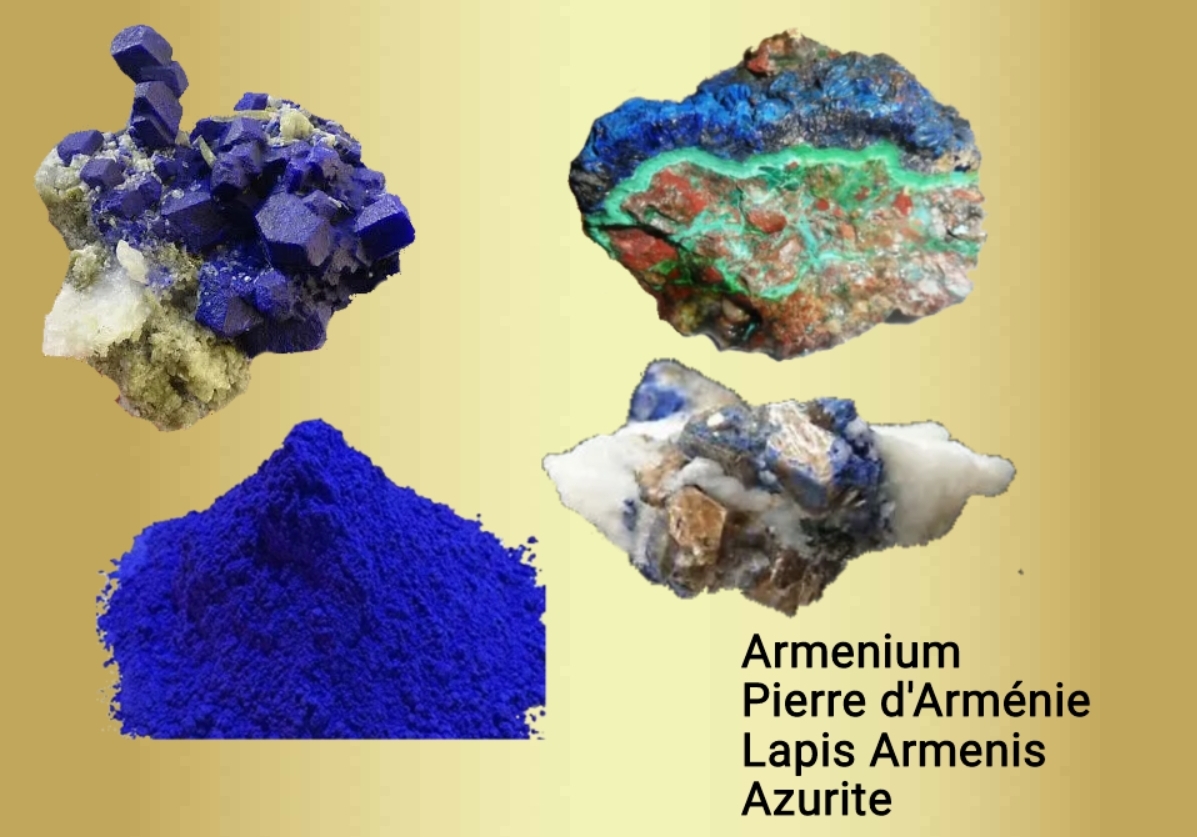

“A parchment manuscript mentions the ancient Children of the Sun who settled on the plateau on the left bank of the Arax River. This area was called Arévik” … (A. Bakunts)

“…I too wish to be called a Child of the Sun. Indeed, I am a Child of the Sun” … (M. Saryan)

More in the next article to come.