Details about ancient architecture and sculpture are revealed to us through archaeological excavations and the writings of historians…

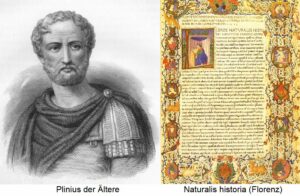

Pliny the Elder, a Roman naturalist and general (circa 23-79 AD), who authored the encyclopedic Natural History in 37 volumes, also offers significant insights into the historical geography of Armenia and the unique veneration of Anahita, the mother goddess of the Armenians.

Within the Armenian context, during the Christianization process, Armenian literature features depictions that urge the demolition of luxurious and grandiose places of worship, including their ‘lofty fortified walls.’

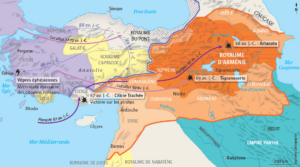

In the temple of Anahita, situated in the Anahiti region of Upper Armenia (near Erzurum and Erzincan), he describes the statue made of gold as the first one fully cast in solid gold

“It is said that the first statue made of solid gold, without any hollow areas, even older than the solid bronze statues known as holosphyrates (hammered entirely by hand), was erected in the temple of the goddess Anaïtis (refer to Chapter V, section 20, to determine the region associated with this name). The inhabitants of the region held the statue in great reverence.”

“Cicero and Pliny also refer to Anahita of Eriza:

Their accounts suggest that the people attributed great significance to their goddess.

When Lucullus entered Armenia, the Armenian people were in great turmoil; more than anything, they were concerned about the temple of Anahita, where the goddess was honored with ‘an extremely grand and solemn worship,’ as Cicero explained,” wrote “Bazmavep” in 1914.

The esteemed Garegin Levonyan examined the ancient traditions of Armenian sculpture, with one of his articles, published in issue 5 of 1913 of the illustrated magazine “Guegharts” (special international issue, pages 153 to 159, Venice, Mechitarist printing house), presented below with some edits.

“… Especially because he was also taking some of the magi with him…”

Our previous article covered Trdat’s journey, accompanied by magi, from Armenia to Rome for his coronation, a journey that took 9 months. Below is the remarkable study on the group of horse sculptures that were gifted to Nero during this visit.

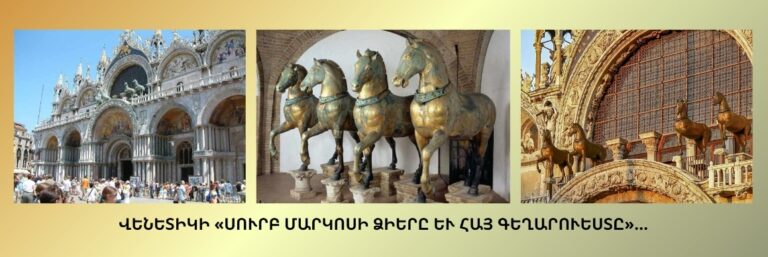

The Horses of Saint Mark and the Influence of Armenian Art

Under this rather unusual title, our readers will uncover a captivating tale that traditionally links to our pre-Christian art.

In Venice, the famous and unparalleled Saint Mark’s Basilica is made even more majestic and triumphant by the four magnificent gilded bronze horses, set on separate pedestals above the main portal of the façade.

These marvelous horses are mentioned even before one arrives in Venice. It is also said that Armenians might have some connection to these artistic masterpieces.

For us, such an interesting question could not naturally go unnoticed, and we are therefore in a position to share with the readers of ‘Guegharts’ both the result of our personal impressions and the information we have gathered from various sources, while finally adding our rather bold opinion.

The first thing a person does upon arriving in Venice for the first time is to head to Saint Mark’s Square (Piazza di San Marco), which feels more like a grand salon, surrounded by majestic columned palaces and the basilica, than an ordinary square. The initial impression is so overwhelming that the art lover doesn’t know where to fix their gaze: the palaces, the massive bell tower, the extraordinary clock, or the Basilica of Saint Mark, adorned with its four magnificent golden horses and its brilliant mosaics.

These noble horses…

They once adorned the triumphal arch of Nero, embodying all its glory, arrogance, and extravagance, twenty centuries ago.

After decorating Rome for more than four hundred years, they were transported to Byzantium by order of Emperor Constantine the Great, for the inauguration of the new capital on the shores of the Bosphorus (4th century). In the early 13th century (in 1206), one of the famous Venetian doges (Marino Zeno) brought them to Venice to further adorn a city already sumptuously decorated like a young bride.

At the zenith of imperial glory, just like Nero, Napoleon Bonaparte, upon seeing these horses in Venice, proclaimed, “Let them be mine!” and had them taken to Paris (1797). They were returned to Venice in 1815, where they have remained ever since.

Here is the brief history of the Horses of Saint Mark.

What a beautiful account of this journey, as narrated by the Italian poet of Armenian origin, Vittoria Aganoor, in her “Eternal Dialogue”.

Here they come upon the Bosphorus,

Vittoria Aganoor, «Eternal Dialogue»

The majestic ones. On their masts wave

The crimson and gold banners, adorned

With freshly bloomed laurels…

Bronze horses, how many triumphs

Have you witnessed, how many epic, thundering dreams.

These horses are splendid, and their history is intriguing, but what could their connection to the Armenians be, one might wonder. This is the question we will examine now.

Where did Nero acquire these horses? Experts assert they are not Roman creations. Notably, ancient Roman historians already recorded that they were a gift from “the Armenian king Tiridates”.

There are two prevailing views: one claims that Tiridates or Tiridates (Arshakuni) brought the horses to Nero, while the other suggests that Tiridates the Great delivered them to Constantine.

«One ancient document mentions these bronze horses in connection with Tiridates, as detailed by Victor Publius in his description of Rome’s E district. Another anonymous writer, contemporary with Emperor Honorius or G. Valentius in the mid-5th century, also refers to Tiridates: Equum Tiridatis Regis Armeniorum. It is worth noting that not only the horses in Venice but also those still in Rome bear a strong resemblance to those referred to as “the horses of Tiridates” on Monte Cavallo», writes H. Gh. Alishan in his work “Ayrarat.”

« When we mention the imperial, our thoughts inevitably turn to the royal », continues the author of Ayrarat, «and it is not enough to merely regard Tiridates’ gifts as elegant offerings, but also to consider what historians have left unmentioned. Yet the Italians have a tradition, and some local Venetian historians, in their writings, assert that the Armenian King Tiridates (whom Nero viewed as Parthian) gifted these four famous gilded bronze horses to the emperor, which frequently adorn the elevated façade of the unique Saint Mark’s Basilica, on the famed square of our Adriatic capital…»

It is not imperative for us to ascertain which of the two Tiridates brought these horses to Rome, whether it was Tiridates referred to as Tirith or Tiridates the Great; what truly matters is that they originated from Armenia. If it had been Tiridates the Great, our historians would certainly have noted this gift in their accounts of his journey to Rome with the Illuminator, as Agathangelos records. Agathangelos has recently faced significant criticism (Langlois, Gutschmid, Tashjian, Sargsyan), which has undermined his historical position and even displaced him from his role as “Tiridates’ secretary”. Consequently, it is highly probable that it was Tiridates Arsacid, known as Tirith, who traveled to Rome and was presented to Nero. Given that our historians typically do not mention Tirith, there was no expectation of this gift being documented. On the other hand, notable Roman historians such as Pliny, Tacitus, Cornelius, and others recount Tirith’s triumphant entry into Rome and Nero’s ceremonial reception. Based on these sources, M. V. Chamchian composed a splendid passage in the first volume of his “History” (page 324), which we present here with some edits for brevity.

Tirith, escorted by numerous Eastern attendants and three thousand Armenian and Persian horsemen, along with several Romans, made the journey overland. He refused to cross the sea by ship, as Pliny mentioned, because according to the Magi’s religion, it was forbidden to taint the sea with impurities or even to touch it. Additionally, he had some Magi with him. Traveling by land, Tirith took approximately nine months to arrive, incurring significant expenses, not only for himself but also for the Romans. Nero had decreed that in every city where Tirith passed, he should be welcomed with grand celebrations and sent off with honors. Everywhere, the streets and squares were decorated, and he was received with splendor and accompanied by the songs of artists. All his and his servants’ needs were generously provided for.

As Tirith neared the borders of Italy, Emperor Nero, informed of his approach, prepared opulent garments for him and sent chariots to greet him, for he had traveled on horseback to Italy. Tirith wore a golden helmet and was magnificently dressed, with a majestic bearing according to Dio, and an imposing demeanor, yet thoughtful and vigilant, which made him highly regarded by the Romans wherever he went.

When Tirith arrived in Naples, Emperor Nero himself came to greet him. In Nero’s presence, Tirith was asked to surrender the sword he carried at his waist, as this was not permitted before the emperor. But Tirith refused, for, according to Tacitus, he had received an order from Darius not to display submission to the Romans and to maintain the dignity and authority of the Arsacids. To avoid any suspicion from the Romans, Tirith nailed the sword to a pillar, as Dio recounts, and bowed to the emperor in greeting.

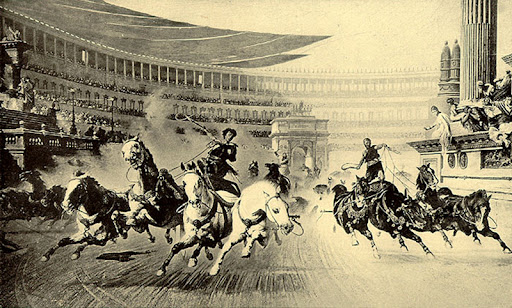

Impressed by this gesture, Nero received him with great courtesy and respect, and after extensive discussions, ordered wrestling matches and beast fights in his honor in the city of Puteoli. Tirith, seated next to the emperor at the beginning of the games, wishing to make the spectacles more engaging, requested a large bow. He shot an arrow from the podium at the beasts below, killing two strong bulls with a single shot, which evoked great admiration from the spectators.

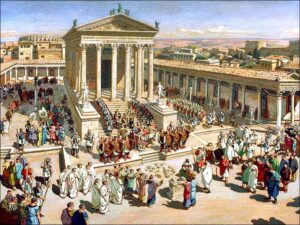

Nero then escorted Tirith to the imperial city of Rome, which had been partially refurbished, with the desire to crown him there. According to Tacitus, the entire city gathered to greet the emperor and Tirith. Shortly after, Nero decided to organize Tirith’s coronation ceremony and ordered the grand square to be adorned with torches, lanterns, flowers, and garlands, where a large crowd had assembled. Part of the nobility, dressed in white and crowned with laurel wreaths, formed a circle in the center of the square, while soldiers in decorated armor stood on each side. Their weapons and banners shone under the dazzling lights.

Having arranged everything during the night, at dawn, Nero arrived with great fanfare, accompanied by the praetors and his personal guard. Nero wore a golden toga, the one he wore on triumphal days, and seated himself on the principal throne. Tirith then arrived with his companions, passing through the ranks of soldiers aligned on either side. Upon reaching the throne, he bowed and greeted the emperor with due respect, and the kings who accompanied him did the same. Then, the entire crowd in the square burst into cheers with a unified shout of joy, so much that Tirith was filled with wonder.

At that moment, Nero addressed him: “You have done well to come here before me, to benefit from my generous favor… Behold, I make you king of Greater Armenia.” With these words, Nero instructed Tirith to sit before him on the throne prepared for this purpose. And as he took his seat, Tirith was once more greeted by the loud cheers and celebrations of the crowd.

The historian then details the ceremonial presentation at the Theater of Pompey, “by order of Nero and the entire Senate in honor of Tirith,” where “Nero himself appeared on a chariot, dressed in an embroidered toga and green garments, driving the chariot himself and circling with grandiose splendor, accompanied by music and artistic songs.”

“Following the ceremony, King Tirith thanked Emperor Nero for his generosity… and, after receiving substantial gifts from him, HE RETURNED THE FAVOR WITH DIGNITY, before returning honorably to his kingdom in Greater Armenia.”

In the passage described above, drawn from Roman historians and transcribed by Chamchian, which is inherently fascinating to us and could serve as valuable material for contemporary historical drama, the most crucial aspect for our article is the final sentence, noting that after receiving gifts from Nero, Tirith reciprocated. This is where the issue concludes… as we have already mentioned earlier, citing the same Roman source, Nero’s horses were a gift from King Tiridates of Armenia — “Equum Tiridatis Regis Armeniorum.”

The original text by Tacitus on this matter was published by H. J. Avger in the first issue of this year’s “Bazmavep.”

We have pointed out that for our article, the critical point is not which of the two Tiridates brought these horses, but that they were brought from Armenia. Now, a new question emerges: where did they come from in Armenia? Were they imported from Greece, or are they Armenian works of art? No one dares to label these magnificent sculptures as Armenian creations, but it is believed that they are “war trophies brought back from Greece by our brave ancestors, Artaxias or Tigranes, works by the great Greek sculptors Praxiteles and Lysippus” (Alishan).

It is certainly plausible that the philologist’s opinion is accurate, but neither in the works of Lysippus nor Praxiteles, nor in the history of Greek sculpture as a whole, do we find specific statues of horses. However, Khorenatsi clearly mentions the statues that Artaxias and Tigranes brought back from Greece and how they positioned them, specifying that they were statues of gods.

“Artaxias brought back from Greece the statues of Zeus, Artemis (Diana), Athena (Pallas Athena), Apollo, and Aphrodite (Venus), and had them brought into Armenia…” (Khorenatsi, B. 12). “And after assembling the Armenian armies, he (Tigranes) went to face the Greek armies… The first thing he did was to build a temple… He set up the Olympian statue of Zeus in Ani, and that of Athena in Til, and that of Artemis in Eriza, and that of Apollo in Bagayaritch…” (Khorenatsi, B. 14).

Without refuting this view, we propose a bold new hypothesis: these bronze horses could also be creations of Armenian art, sculpted and cast within Armenia’s borders.

Let us now review the favorable evidence that supports our hypothesis:

A. Sculpture in Armenia.

We still regret that sculpture was overlooked in our article “Introduction to the History of Armenian Art,” and we feel the need to discuss this art here.

Sculpture has been the most unfortunate of the arts in Armenia compared to others. We use “unfortunate” not because it was lacking or impoverished, but because it was the most targeted during the early Christian period and was unable to pass down its ancient masterpieces to later centuries.

It remained unfortunate up to the present day, as it is the least discussed of Armenian arts, almost never mentioned, with the entrenched belief that “we had no sculpture.” And if we had nothing, there would naturally be no studies on it. Leaving the detailed results of our research on this topic for the next volume of “Art,” continuing the same article, we will briefly state this: According to the history of Armenian mythology or pagan religion (Emin, Alishan, Kostanian, Cheraz, Gelzer, H. B. Sargsian), it is well documented that pagan Armenia, in addition to imported gods, had its own unique Armenian gods, which are not mentioned in the mythologies of ancient peoples. We see these statues of gods and heroes set up in various parts of Armenia. The question then arises: where were these metal statues made and cast if not in Armenia? Where were Armenian coins with their reliefs minted, if not in the country itself and not abroad? “And he minted coins with his own portrait,” Khorenatsi writes about Artaxias I (B. 11).

If we accept that the art of sculpture existed in pre-Christian Armenia, why couldn’t we also accept that these four bronze horses originated from Armenia?

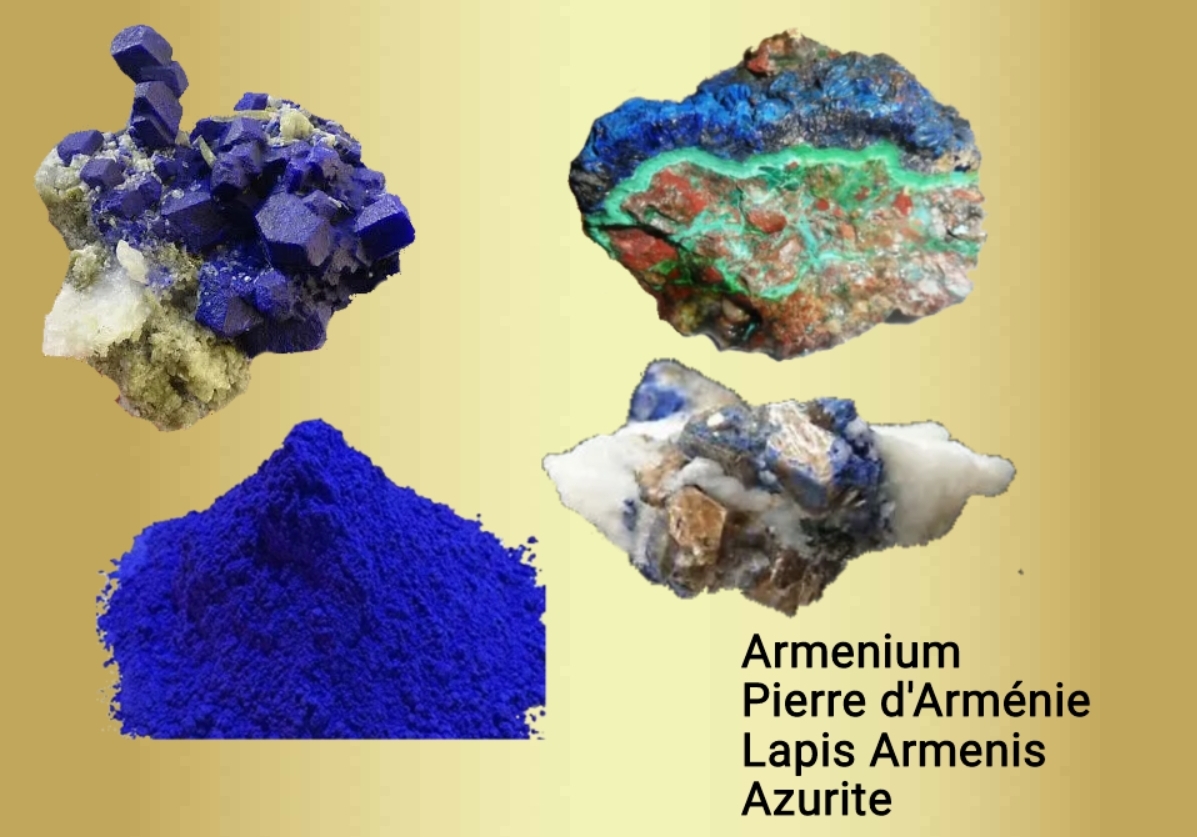

B. Sculpture Resources.

The materials essential for sculpture, like clay and metals, were readily available in ancient Armenia and were indeed utilized. There is solid evidence supporting this: The clay was so well-regarded that it was known by other nations as “Armenian clay”: “We are mentioned in certain medical texts that reference a substance called ‘Armenian earth’ by Galen, described as ‘clay’ or ‘earth’ in the original script, and also referred to as ‘Armenian stamped earth’ because it was part of the composition of the bolus armeniacus, a reddish clay known among the Turks as ‘kil ermeni’… (Injijian, ‘Antiquities, A., 181).

Mining is confirmed by brief mentions in our historical texts: “The king (Tiridates) ordered a festival of joy and released those who were imprisoned and those in the mines” (Zenob). Moreover: “He ventured to the mountain where iron and lead were mined” (Buzand).

Mines of silver, gold, and copper are explicitly mentioned by both Armenian and foreign writers.

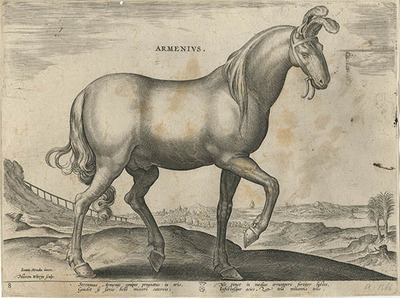

C. Armenian Horses.

The horses of ancient Armenia were highly esteemed not only within their own borders but also far beyond: “A multitude of horses comes from this region (Armenia), unmatched by anything in Media,” reports Strabo.

The profusion of horses in Armenia is also proven by this historical fact: Armenian kings frequently paid their tribute to the Persian court in horses. Xenophon even described a plain in the Euphrates basin as a “Hippodrome,” highlighting the vast numbers of horses. Armenian historians often extol their cavalry, known as “ayrudzi.” This is also acknowledged by foreign authors. “Artavasdes showed Antony a force of six thousand cavalry, all well-armed and trained, which he led into battle against the Medes,” Strabo recounts (Injijian).

Let’s also remember Tirith, who traveled for nine months from Artashat to Rome with his “three thousand armed horsemen.” Special attention is given to the purebred or “wonder horses” owned by Armenian royalty and generals. “And Ervand, after riding through the arena on his horse, exited and went to his city” (Khorenatsi, B., 46).

“The two horses of Tiran II were faster than Pegasus himself, not just walkers on the ground, but runners in the air,” (Khorenatsi, B., 62).

“At that time, Moushegh (Mamikonian) had a horse. And when the Persian King Shapur drank wine in his pavilion… he would say: let the wine be given to the white horse,” (Buzand, E, 2). Moushegh was so well-known for his white horse that after his death, his image was carved on the horse. “Assyrian craftsmen carved the image of Moushegh on his white horse on a monument near the river, with the Huns at his feet, and the locals still call the place ‘The Gate of the Huns,’” (Mesrop of Yerznka 20), (Injijian).

Bardic songs also celebrate the “magnificent horse” of Artashes II and the hunting steed of his son, Artavazd.

The vast array of accounts about swift, light, flying, and aerial horses in Armenia serves as irrefutable evidence of the high regard for this noble animal in our past and the improvement of its breeds. (There was even a manual on horsemanship in Armenia: “On the Breeds and Lineages of Horses and the Raising of Foals.” Refer to “Bazmavep,” 1867, page 353.) As the most noble and valuable product of the country, horses were considered the most fitting gift for foreign courts, as well as for Armenian nobles, generals, and high officials. Even in pagan times, white horses were sacrificed to the gods.

“Tiridates’ father, Khosrov, in gratitude for his victory over the Persians, sacrificed white bulls, white rams, white horses, and white mules at the shrines of his homeland,” reports H. V. Hatsuni in the sacrifices section of his book “Feasts,” citing Agathangelos. Faustus of Byzantium mentions that Arshak II gave Bishop Khagh “many horses from the royal stables, equipped with royal harnesses and golden bridles.”

These favorable circumstances suggest that the horses of Saint Mark presented to Nero by Tirith were the most prized gift from Armenia, reflecting the nobility of Armenian horses and the wealth of the Arsacids with their bronze statues.

Perhaps our view is bold, perhaps we are enthusiastic, but let our hypothesis be expressed until future scholars provide new evidence to validate it. A decade ago, there was a completely different view on Armenian architecture. Today, the East is recognized as the source of enlightenment. We won’t progress with timidity.”

Garegin Levonyan, Venice